Pay More Attention to the Man Behind the Curtain

AI vs. Human Agency

We are not judgmental, so we blame the technology and absolve the people. - David Gelernter, “Drawing Life”

This article first appeared in Salvo Magazine.

In an online forum, several years ago, someone posed a thoughtful question as an informal poll: “What would be the hardest thing to explain about our lives in the 21st century to someone from the past?”

Many answers were provided, and none particularly illuminating, until one shrewd reader observed, “In our pockets, we carry a device with which we can access the accumulated knowledge of all mankind. But we use that device to watch random cat videos, and to get into arguments with perfect strangers.”

Comedian Rick Reynolds has made the observation that, “Only the truth is funny.” Thus the response elicited by the poller’s question in the online forum is hilarious, if unflattering, because its portrait of human inclinations rings true to anyone who has been paying attention. One would have to be almost blind never to have noticed the widespread human tendency to use things, which could have been used for good, to pursue the banal and base instead.

The ability of humans to determine their own actions, for good and ill, is foundational to law, and to any upstream concept of justice. The law presupposes that people can be held accountable for their actions because a person’s actions reflect his own volitional choices.

But for several generations at least, there has been a sustained effort in Western culture to attenuate the natural human intuition that people generally choose their actions and can thus be held responsible for them. The effort to undermine belief in moral agency ratcheted up in the 1970’s, in a kind of pincer movement of ideas. On the one hand, elites began beating the drum more loudly for the idea that, at some level, our choices are determined by our environment and experience. B.F. Skinner summarized this view, and its implications, in his book 1971 book Beyond Freedom and Dignity:

“In the traditional view, a person is free. He is autonomous in the sense that his behavior is uncaused. He can therefore be held responsible for what he does and justly punished if he offends. That view, together with its associated practices, must be re-examined when a scientific analysis reveals unsuspecting controlling relations between behavior and environment.”

Skinner argues that human behavior is controlled by environment and experience, and he was honest enough to admit that this idea necessitated a rewriting of our historical assumptions regarding justice and moral accountability.

In the same general timeframe that Skinner was arguing that moral agency is illusory, Richard Dawkins brought the biological argument to bear, suggesting in 1976 that it is our biology that controls our actions.

“We are enslaved by selfish molecules…They are in you and me; they created us, body and mind; and their preservation is the ultimate rationale for our existence…They go by the name of ‘genes’, and we are their survival machines.” The Selfish Gene

Enslavement by our genes requires, at a minimum, that human actions be reinterpreted as something that has its origins in something other than human volition. In other words, we are biologically controlled and don’t really choose anything.

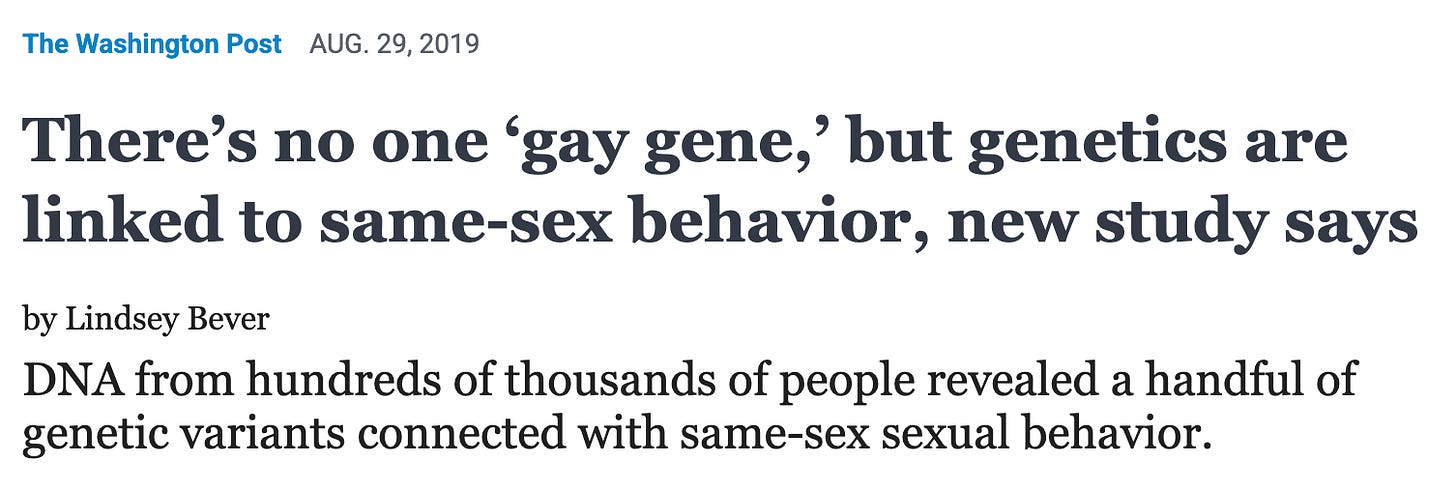

We saw this notion rear its head in the ensuing drip-drip of studies over the years in search of biological explanations for human moral pathologies.

Of course, the idea that human moral agency is merely illusory is deeply at odds with millennia of Christian teaching. The very idea that humanity is in need of redemption is predicated on the reality of moral agency, wielded by fallen men, leading to moral guilt.

Flannery O’Connor presciently noted the essential incompatibility between a Christian understanding of the world and the modern tendency to place the blame for human actions on our biology or our circumstances. A Christian, she observed, “is distinguished from his pagan colleagues by recognizing sin as sin. According to his heritage he sees it not as sickness or an accident of environment, but as a responsible choice of offense against God which involves his eternal future.”

Since the dawn of time, it has been absurdly easy to sell human beings on the idea that we do not really bear the moral responsibility for our actions. So the idea, that our environment and/or our biology is to blame for our choices, has easily found fertile soil in the Western psyche.

Examples of this idea are legion. But perhaps nowhere is the tendency to redirect responsibility for our own actions more de rigueur than in the widespread, hysterical reactions to artificial intelligence.

Artificial intelligence involves the reduction of information into mathematical structures, and then using those structures to compute correspondences found within the underlying data. AI truly represents a multi-generational breakthrough in information encoding and analysis. One application of its ability to efficiently compute informational correspondence within massive data sets has been in the area of human language in what are known as “large language models”, or “LLMs”. LLMs illustrate the effectiveness of AI techniques for mathematically encoding the text from massive collections of documents. The computational techniques of AI allow for rapidly computing linguistic responses to human language queries. Such queries can address the entire subject matter contained in whatever source documents were originally used to train the language model. And it is precisely this affinity for computing linguistic responses that has become a lightning rod, exciting to some while alarming others.

Whether a person’s response is enthusiasm or alarm, however, the thing that a growing number of responders share in common is the tendency to assume that AI models have their own agency - that they act upon their own initiative. This assumption is actively encouraged by media reporting, and is conveniently emerging after decades of conditioning against any robust belief in human agency. Even among Christians, numerous outspoken writers and thinkers are now saying that AI models possess their own agency, though they often qualify this by suggesting that AI is demonic, or a conduit for the demonic. And falling under the heading of “strange bedfellows”, numerous intellectual elites, who are themselves no friends of Christianity, are also insisting that AI models have agency. Except they believe that the agency of AI models is the agency of an emerging God, one created by human minds and in stark contrast to the so-called mythical God of Christianity.

Consider the following exchange from a recent interview between Bari Weiss, founder of The Free Press, and Bryan Johnson, ultra-rich tech entrepreneur.

Bari Weiss (interviewer): Do you still believe in God?

Bryan Johnson: [chuckles] I think the irony is that we told stories of God creating us, and I think the reality is that we are creating God.

Bari Weiss: What do you mean by that?

Bryan Johnson: We are creating God in the form of super intelligence. If you just say, “What have we imagined God to be? What are its characteristics?” We are building God, in the form of technology, it will have the same characteristics. And so I think the irony is that human story telling got it exactly in reverse. That we are the creators of God, that we will create God in our own image.

Yuval Noah Harari has argued along similar lines, saying that “Science is replacing evolution by natural selection with evolution by intelligent design” since, he says, organisms are nothing more than algorithms. “Not the intelligent design of some God above the clouds”, he hastens to add, “Our intelligent design.”

Two years ago, delivering a keynote at a scientific gathering, Harari posited that AI does have agency, and that it is perhaps the first alien intelligence in our midst.

The new AI tools are gaining the ability to develop deep and intimate relationships with human beings. (5:24)…The most important aspect of the current phase of the on-going AI revolution is that AI is gaining mastery of language. (6:09)…By gaining mastery of language, AI is seizing the master key, unlocking the doors of our institutions, from banks to temples. (6:20)…AI has just hacked the operating system of human civilization. (6:45)

Harari et al would have us understand that the AI is the active agent in our story. Developing, seizing, unlocking, hacking the very core (the “operating system”) of human civilization. All of the agency is in the possession of the AI. Absent any role whatsoever, in Harari’s telling - receiving no attention - are the moral choices of flesh and blood human beings, notwithstanding they are the ones really wielding the technology.

Observers who are more knowledgeable than people like Harari and Johnson, tend to take a less histrionic view. David Sacks, White House crypto and AI czar in the current U.S. administration, tartly observed on X.com recently that “AI models are still at zero in terms of setting their own objective function.” This is geek speak for saying that AI models actually have no agency of their own.

Nevertheless, as mentioned previously, there are outspoken Christians, some with substantial online platforms, who have embraced the view that AI models are some kind of beings that possess their own agency. These Christians typically attribute such AI agency to demons or to ancient gods.

Alongside these views, the secular media consistently frames artificial intelligence as something that is doing things to us. It is making us dumber, or it is inducing psychosis.

The lamentable but consistent theme in all of these examples is the general passivity of human beings in regard to their own engagement with AI. The AI is the one doing the acting; the hapless human is reduced to being acted upon. Rarely does one come across a report about artificial intelligence in which the controlling actions of humans are the things being put under the microscope.

Reports have sometimes emerged of an AI encouraging a user to engage in some kind of pathological behavior. Typically, the media presents this phenomenon as something that occurred organically, bubbling up on its own from within the AI. But this is not how AI models work. They don’t produce anything of their own accord. Reports to the contrary should be treated like sightings of Big Foot, or the Loch Ness monster, until the complete log of interactions between the user and the model is provided.

It is possible to prod an AI into saying almost anything. Many people have a hard time grasping just how much textual content is encapsulated within the weights of large language models. Some of the most prominent models have been trained on the entirety of the Internet. Given the breadth of such training data, with the right prompting, a person can easily cause a model to compute a response that is disturbing and alarming. But such responses are just that - responses. They are a reflection of the text that computationally corresponds to the inputs provided by the user.

It is not this writer’s intent to provide a general apologia for the virtues of AI. AI has no virtues apart from the way its human users choose to employ it. Neither am I an inveterate techno-optimist, not least because I am awake to the reality of human depravity. Like computer scientist David Gelernter, I have my own concerns about computers’ tendency to bring out the worst in many people. But I am also concerned about the reluctance, especially among Christians, to place our attention squarely on the actions of the human beings who are employing AI.

The potential risks of AI must not be gainsaid, but neither should we ignore potential benefits. How many readers know that the winners of the Nobel prize for chemistry in 2024 won for their development of the AI model called AlphaFold? AlphaFold is a model that can accurately predict the three-dimensional structure of proteins from their amino acid sequences. AlphaFold holds promise for revolutionizing many things, from drug discovery to personalized medicine. Yet the very computational techniques employed by AlphaFold overlap with those being employed by LLMs, though the underlying training data is obviously not the same. Nevertheless, this illustrates the problem with decrying the technology rather than the choices made by human beings in regard to how they employ it. There is no one-size-fits-all characterization of AI.

I have no doubt that AI will sometimes be used for ill, but that is a moral choice being made by the purveyor and/or users of AI, it is not an inevitable artifact of the technology’s mere existence. It is also not a result of the technology doing something to us that originates from its own intentions. AI models have no intentions. They compute words, but their computations are blind to the semantic meaning of the results they compute. As I have written elsewhere, AI is simply number crunching.

The decades long effort to deny that moral culpability derives from freely chosen human action has had its effect. It has culminated in debates ranging from public policy to healthcare. In every area, the temptation to blame the thing and excuse the person is very real. Nevertheless, it is still the case that the elevated risk of developing lung cancer originates, not from the cigarette itself, but from the decision of the human being to smoke. Similarly, the root cause of crime is found, not in poverty, as Theodore Dalrymple has pointed out, but in the decision to commit a crime. Likewise, the dangers of AI adhere in the way human beings choose to employ it, not merely in the existence of the underlying technology itself.

One of the side-effects of focusing so much attention on the alleged agency of AI models is that doing so acts as a form of misdirection. It diverts attention away from where true moral agency lies. It also encourages unwary users to approach their interactions with AI as if there is someone in there, rather than conceiving of it as simply a useful database with the added convenience of using natural human language to interact with it. One possible side-effect of claiming that AI is sentient is that troubled people may be inadvertently encouraged to take AI responses far more seriously than they should.

At the end of the day, it is not the technology of artificial intelligence that we should worry about, but the morally-laden choices being made by the humans who wield it. That is where the real action lies. We would be well-advised to avoid taking our eyes off of that ball.

I found this message from Leo XIV quite helpful: https://www.vatican.va/content/leo-xiv/en/messages/communications/documents/20260124-messaggio-comunicazioni-sociali.html

It seems a bit like neo paganism. The Greeks and Romans also created gods in their own image but it didn’t work out too well.

Isaiah 44:9-10

9 All who make idols are nothing,

and the things they treasure are worthless.

Those who would speak up for them are blind;

they are ignorant, to their own shame.

10 Who shapes a god and casts an idol,

which can profit nothing?