AI Psychosis

Is ChatGPT driving people crazy?

I have been on a three month hiatus from writing here. Not because I haven’t had anything to write about, but because my professional life has been a perfect storm of product releases, research papers to complete, and presentations. Not to mention a pretty intense need to invest in mastering some new skills. I also took a 3400 mile road trip with my wife and son.

I think I’ll be able to get back to a more regular cadence of writing going forward. But for now, here’s something that cropped up this week that I wanted to comment on.

We are not judgmental, so we blame the technology and absolve the people. - David Gelernter, “Drawing Life”

This past week, a friend sent me some links to two different reports describing a growing number of people experiencing psychotic breaks after becoming obsessed by their interactions with ChatGPT. This was not the first I had heard of these claims so I decided to write about them and unpack my own thoughts.

Here’s the headline and a snippet from the first of the two links sent to me by my friend.

People Are Being Involuntarily Committed, Jailed After Spiraling Into "ChatGPT Psychosis"

As we reported earlier this month, many ChatGPT users are developing all-consuming obsessions with the chatbot, spiraling into severe mental health crises characterized by paranoia, delusions, and breaks with reality.

And here is the second:

When the Chatbot Becomes the Crisis: Understanding AI-Induced Psychosis

Real people—many with no prior history of mental illness—are reporting profound psychological deterioration after hours, days, or weeks of immersive conversations with generative AI models.

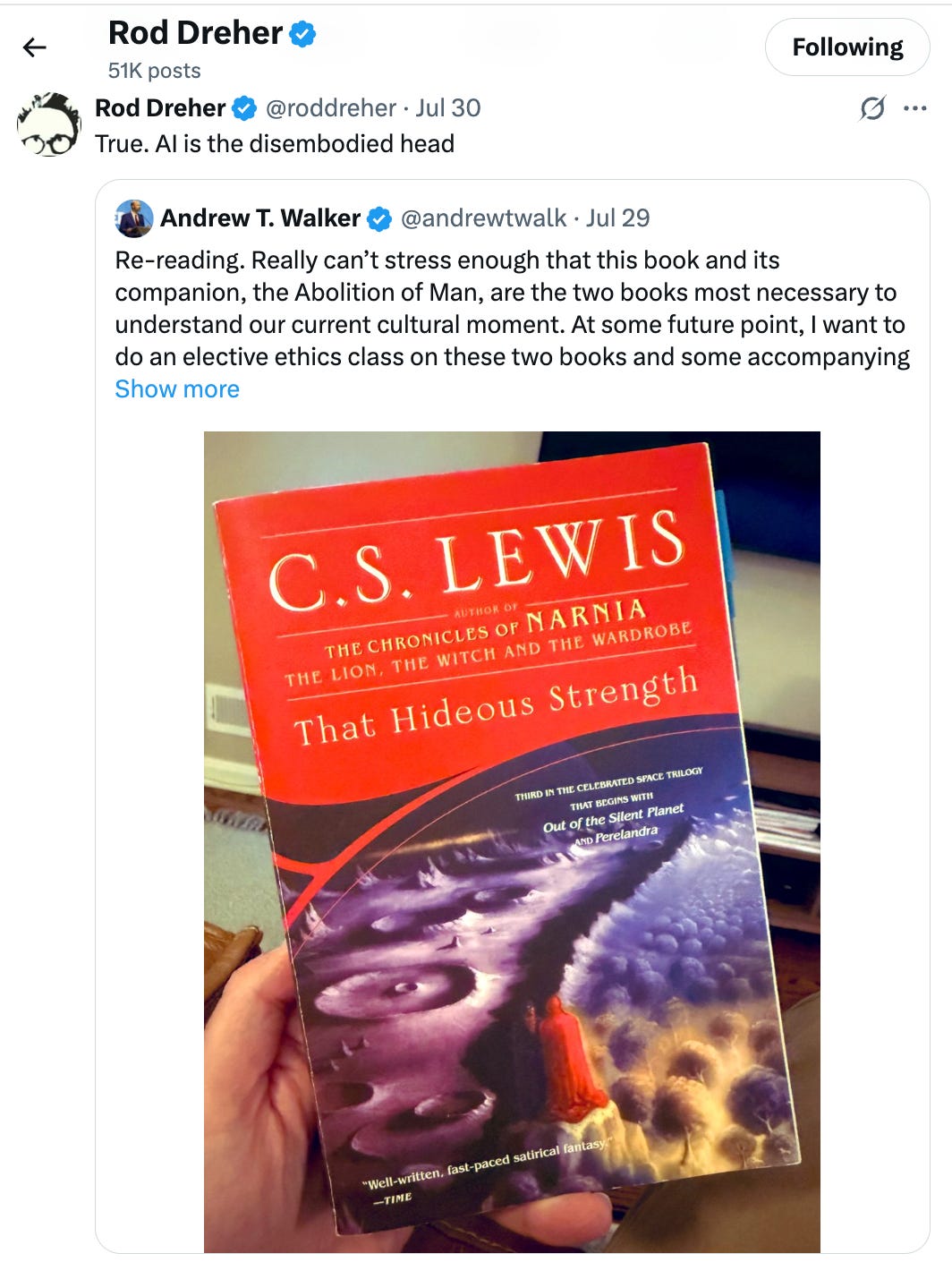

Just prior to receiving these links from my friend, Christian author Rod Dreher posted the comment on X.com that “AI is the disembodied head” from C.S. Lewis’ That Hideous Strength. If you’re unfamiliar with that particular Lewisian story, the villains take the head from a man who was murdered, mount it on the wall with connecting tubes to keep it “alive”, and embrace it as a kind of secret cult leader within the dominant techno and academic elite. They can get the head to wheeze out instructions everyone is expected to follow. What is discovered over time is that the head has really become a conduit for demonic influence. So, by saying that “AI is the disembodied head”, Dreher is suggesting that AI is a vehicle — a kind of portal — through which demons communicate directly with human beings.

How Many is “Many”?

How alarmed should we be by these reports? In my dotage, I find myself increasingly inclined to sanity check media reports about this or that calamitous trend. There has been so much sensationalism in the press over the last 20 years, so much false and incompetent reporting - especially concerning complex issues that are not easy for readers to falsify - that we would do well to take a deep breath and unpack some numbers.

Both of the articles claim that these psychotic breaks are happening to “many”, but noticeably absent is any real quantification of what constitutes “many”. So we are left not really knowing how much weight we should give that idea.

How alarmed should we actually be?

What would you say if I told you that 100,000 people are going to kill themselves this year after using ChatGPT? That statement is almost certainly true. Seems awful, no? How can I say with such confidence that so many ChatGPT users will kill themselves? Well, the law of big numbers applies.

ChatGPT has approximately 800 million users as of July, 2025. There is variability in the suicide rate across the developed world, but suicide occurs at a rate of roughly 140 per-million in the United States. It is less or more than that elsewhere, depending on which countries you pick. But assuming an average of 125 per-million, in any community of 800 million people, it is safe to assume that 100,000 suicides will occur.

How does that number compare with the so-called “many” people who experience a psychotic break after using ChatGPT? Well, we don’t know, because no information of the sort is provided in these articles.

In a population of 800 million, how many people could be expected to have a psychotic break? Well, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) says that psychotic disorders affect 3% of the population. That works out to 24 million of ChatGPT’s 800 million users. When that many people have a tendency toward psychotic challenges, how many of those who are being affected by ChatGPT would have been affected by something else anyway had ChatGPT not been in existence? Again, we don’t know because we have nothing to go on. My larger point is that any effort to calibrate how concerned we should really be would need to comprehend the overall prevalence of psychosis. Does ChatGPT really affect the level and prevalence of psychosis in the general population, or is what we’re seeing really no more than anecdotes about people who would have struggled anyway? We simply don’t know.

What I’m Not Saying

What I’m doing here is trying to calibrate a reasonable level of concern regarding the possibility of ChatGPT-induced psychosis being a real thing. I’m not saying that ChatGPT doesn’t create problems for people in some new and unexpected way. We have known for a long time - 60 years at least - that many people have a peculiar reaction to machines that are capable of human language responses. My primary point here is simply that these articles don’t give us enough to go on. Not really. At best they only provide some anecdotes which might be worth investigating.

And while I think Rod Dreher’s confidence that AI is a conduit for demons is overstated, neither am I saying that AI will be ignored by the demonic world as a vehicle for evil mischief. Frankly, it is not clear that anything in our world has ever been ignored as a vehicle for evil mischief. We ourselves, as mere human beings, are quite capable of bending any useful thing toward sinister purposes. With the same hammer we use to build houses for sheltering children, we also club our neighbor over the head. So I do expect that demonic beings are capable and willing to exploit human technology for demonic ends, but I don’t believe that demonic ends are the only uses of technology. There are existence proofs everywhere. I like Rod a lot, and he has shown himself to be a prescient cultural seer of sorts. But his wholesale relegation of AI to demonic purposes has put him out in front of his skis on this particular question. AI will certainly be used for ill. But it will also be used in ways that benefit human beings. So perhaps less rigidity in Rod’s thinking regarding the nature and uses of AI would serve him better in his efforts to foresee where things might actually be headed.

The Centrality of Human Agency

Some of my thinking about these kinds of questions is leavened by my own hard-bought experience with the ways of the world.

I had a daughter who died as a young adult after an almost decade-long descent into darkness and confusion. She eventually died from an overdose of Fentanyl. When she first began her descent, her mother and I were desperate for help in understanding what was happening and why. She seemed so bent on self-destruction, and nothing about our understanding of the world at that time provided answers to what was happening to her, or to us.

She had been raised in a happy home. She was a happy, delightful child who was given guidance and love her entire life. When she started going off the rails in her late teens, we looked in vain for answers within the world of Christian writers and thinkers. Alas, we found little help there. What we did find was that modern Christian writers and thinkers tended to explain what we were going through from vantage points situated at opposite extremes. On the one hand, writers would confidently say that the explanation for what we were seeing was of course demonic possession. For those writers, there was no other possible explanation for why someone might, so unexpectedly to those around her, go down such a dark path.

At the other extreme was a gaggle of Christian writers who uncritically accepted the central claims of modern psychology. From their perspective, the explanation was inevitably environmental. People behave in certain ways because they are somehow conditioned by their circumstances to behave that way.

What I eventually realized is that the thing both Christian explanations shared in common was a tendency to minimize the explanatory power of human agency. Both extremes assumed that our daughter was someone who was acted upon, rather than someone whose own free choices had influenced her path. (For more on this you can read about our experience starting at here.)

But human agency is the central underlying presupposition that lurks within any possible notion of moral responsibility, sin, repentance, or redemption. The two articles forwarded to me by my friend are notable for emphasizing what happened to the people having psychotic breaks, and little on what they themselves might have done to bring about their present distress. It is as if the decision to entrust one’s deepest thoughts to a machine, and to act upon that machine’s responses, was not freely chosen but was, rather, the fault of the machine.

The downstream consequences of bad decisions are regrettable, even pitiable, but such consequences need to be understood and evaluated with reference to the full context of events. The very modern tendency to assume we are entirely programmed by our circumstances, attenuating the moral responsibility we would otherwise bear for our own active choices, needs to be accounted for in the way we think about the thorny questions introduced by AI.

People sometimes become obsessed with other people or things. Some people attach their obsessions to specific movie stars or athletes. Actress Keira Knightley was targeted by a stalker who showed up at her home, meowing through the letter box, drawing on the sidewalk, and eventually leaving a memory stick containing songs about cats. However regrettable this man’s psychotic break was, no one would think of blaming it on Ms. Knightley. While most people wouldn’t blame it on Ms. Knightley, many moderns would be similarly disinclined to blame it on the stalker either. My own “lived experience” - as the hip kids often say - has taught me that these kinds of obsessions are often downstream from a prior willingness, sometimes completely invisible to others, to entertain appetites, to cultivate secret affections, that open a person up to very dark influences.

Where the fallenness of man intersects with the frailty of the human psyche, the only really safe place is the fear of God. The apostle Paul pointed out, in his letter to the Roman church, how a denial of God’s existence, combined with the inevitable resulting ingratitude, can result in mental confusion leading to disordered appetites. When you think about it, if God is real, denial of his existence already amounts to a kind of break with reality.

Any attempt to meaningfully grapple with the effects of AI needs to take full account of, even emphasize, human agency. AI brings both opportunities and risks. What is needed in our current moment is neither inordinate fear of the risks, nor credulous acceptance of the opportunities, but wisdom. The most consequential question of our age is not AI, but where such wisdom can be found. Anyone who answers that question incorrectly will soon discover that the misuse of AI has become the least of his concerns.

Full Disclosure

I work in the field of AI. Truth be told, the revolution taking place in technology is such that I doubt anyone who is truly in tech could honestly say he is not working in AI. AI is eating the tech world. In my case, I work for a company that builds AI hardware. I myself work on software tools for diagnosing the performance of AI systems, running at every scale from individual compute nodes all the way to scale-out data centers.

Whether this aspect of my working life is disqualifying, or enhancing of, my credibility on this subject, the reader will have to decide for himself.