Catastrophizing AI

A Christian argument for dialing back on the hysteria

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Arthur C. Clarke

The very first technology venture in recorded history took place on a plain in ancient Babylonia, when the bulk of humanity gathered there and some smart aleck came up with the bright idea of building the world’s first skyscraper.

“Let’s build a tower up to heaven”, he said.

“And let’s do it as an exercise in performative pride1”, he said.

“What could possibly go wrong?”, he said.

Undertaking any task with arrogance and pride is an almost certain way to undermine your effort, right out of the starting gate. First of all, humility is a prerequisite for possessing any ability to learn. But in the case of this particular project, God himself took a dim view of their plans, even though along the way he dropped quite the bomb about the human race’s breathtaking affinity for technology innovation:

“If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. - Genesis 11:6

God himself views mankind’s technological abilities as essentially unbounded. That’s kind of a big deal, and maybe ought to influence our strategic thinking about the future in some way. Just a thought.

Anyway, God threw sand in the gears of technology innovation that day by introducing and imposing entirely new languages on the world. He thereby slowed the pace of technology innovation to a crawl and, for many generations, undermined the ease with which people had previously been able to obtain critical mass for undertaking big projects.

But, over time, significant innovations began to be seen in the world again. And given God’s observation that day - that nothing is impossible for us - we should perhaps not be too surprised. We should also not be surprised, if we have been paying attention, that human beings are often inclined toward the improper application of their own inventions. Often we do this either by giving in to the temptation to worship the works of our own hands (i.e. worship ourselves), or we use our inventions to destroy ourselves and/or others.

I mention all of this because it is tempting, I think, for each succeeding generation to conceive of itself as unique in the history of the world, where facing such challenges are concerned. My larger point, so far, is simply that every generation since the dawn of time has dealt with temptation and challenges related to technological innovation. The long train of human grappling with, and adaptation to, new technology ought to leaven our thinking as we delve into the concerns we might have about artificial intelligence.

However bad we may think we have it in our time, it is hard not to suspect that there were numerous earlier generations that had it worse. The West Point graduating class of 1860 is one generation that springs immediately to mind.

A better grasp of our place within the flow of actual history might stiffen our spine and mute some of the hysteria that seems to increasingly characterize our current moment. I am far from the only person to observe the human difficulty in properly calibrating the challenges we face:

Appreciating what is good in the here-and-now is one of the hardest feats known to man. - David Gelernter, Drawing Life

The world is all agog over recent advances in artificial intelligence. And though the reactions are strong and sometimes borderline hysterical, AI is not the first disruptive technology we have ever encountered. Society-changing technologies have arrived, every few years, for my entire life. Personal computers, VCRs, cell phones, the Internet, genetic engineering, iPods, search engines, and smartphones have each altered our society in noticeable ways.

Any honest observer will have to admit that each of these technologies has introduced both positive and negative changes to the world. On the one hand, people’s lives have been saved, in the midst of a crisis, because someone on the scene was in possession of a cell phone. But on the other hand, VCR's and the Internet have been vehicles for the massive proliferation of pornography. The impact of human inventiveness has never been confined only to the good.

The reason the effect of new inventions is such a mixed bag is because the moral character of human beings is such a mixed bag. We have a modern aversion to fully admitting to human moral agency. Western culture, in particular, has developed a strong bias toward pretending that it is impossible to form clear moral perspectives regarding the character of others. All of the talk among the media cool kids about “my truth” and “your truth” is just symptomatic of a widespread aversion to moral clarity.

The attractive thing about this kind of moral ambiguity is that it relieves us of relational accountability and, so we think, reduces awkward social interactions. But we’re finding out that this approach to reducing social friction only works up until the point that it doesn’t. We’re discovering, for example, that “live and let live” works with the guy who thinks he’s a woman, only until he’s creeping on your children and parading around naked in the women’s locker room.

Much energy has been expended, for several generations now, to convince people of the evils of being judgmental. Such reluctance to make clear moral distinctions is subtly reinforced by the idea that moral agency isn’t real. A person can’t be blamed for his actions, you see, because some circumstance in his life is determining his moral choices. Human agency, according to this telling, isn’t real. Thus, belief in ideas like “poverty is the root-cause of crime” become widespread, and work hand-in-glove with the longstanding cultural pressure to eschew being judgmental.

Technology and innovation have not escaped our current interest in glossing over human moral accountability. David Gelernter, Computer Science professor at Yale, observed years ago that “we are not judgmental so we blame the technology and absolve the people.”2 Nowhere is this more evident than in some of the discussions taking place involving AI.

Our eagerness to offload accountability for how we ourselves employ technology may have reached peak frenzy with the advent of artificial intelligence. Our cultural predisposition to deny our own moral agency fits neatly with, and might even explain, the current eagerness to conceive of AI as possessing an agency of its own.

Orthodox writer and thinker Paul Kingsnorth has written extensively of his view that AI is a demonic intelligence that is being “ushered” into the world by witless people working in the field of AI. Kingsnorth is known for his pungent writing in opposition to what he calls “the machine”, which he uses as a kind of shorthand for all things related to digital technology and the Internet. He conceives of AI as the climactic emergence of a demonic force in the world which has been coming on for some time. Kingsnorth is virulently opposed to digital screens and Internet connections.

When I see a small child placed in front of a tablet by a parent on a smartphone, I want to cry; either that or smash the things and then deliver an angry lecture. When I see people taking selfies on mountaintops, I want to push them off…If there was a big red button that turned off the Internet, I would press it without hesitation. Then I would collect every screen in the world and bulldoze the lot down into a deep mineshaft, which I would seal with concrete, and then I would skip away smiling into the sunshine.

Now, if you find his desire to push people off of mountain tops puzzling, especially considering his self-proclaimed opposition to the harm being done by technology, I share your puzzlement. If nothing else, though, such fantasies highlight the predominately emotional underpinnings of his writing on this subject.

Kingsnorth’s writing combines a gifted facility with language with apparent ignorance of technology itself. He excuses this subject matter ignorance by suggesting that a less rationalistic approach to thinking about technology will offer superior insights.

This is how a rationalist, materialist culture works, and this is why it is, in the end, inadequate. There are whole dimensions of reality it will not allow itself to see. I find I can understand this story better by stepping outside the limiting prism of modern materialism and reverting to pre-modern (sometimes called ‘religious’ or even ‘superstitious’) patterns of thinking.

Kingsnorth conflates rationalism with materialism, while also conflating religion with superstition. In no way do I dispute the idea that reality is more than the material. Nor do I dispute the idea that religious insights are foundational to the way we interpret the world. But I reject the idea that rationality is bound up with materiality, in part because “in the beginning was the Word”. And I reject Kingsnorth’s suggestion that religious insights are fundamentally superstitious. I have no beef with the reality of mystery as an aspect of Christian faith. Finitude, after all, is fundamental to human experience.

I believe that the basic experience of everyone is the experience of human limitation. - Flannery O’Connor

But there is a vast chasm between mystery and superstition.

It is probably worth noting that Kingsnorth consistently ignores the contributions made by technology to human flourishing, even while understandably railing against real societal harms which are easily traceable to some applications of technology.

Totally apart from the emotive arguments Kingsnorth makes, I find his comments about “skipping away smiling into the sunshine”, after fantasizing about disconnecting the Internet and bulldozing all the screens, to be both chilling and appalling. From a purely personal perspective, I am only alive today because of the rapid communications made possible by the internet. My life was subsequently maintained, during a 20 hour emergency improvisational surgery, by digital technology that medical personnel interacted with through the very screens Kingsnorth would have happily bulldozed before skipping away smiling.

Kingsnorth consigns anyone who doesn’t conceive of AI as inherently spiritual and demonic to the outer darkness with all the other ‘materialists’.3 For Kingsnorth, it is seemingly impossible to be spiritual without maintaining a belief that AI is a demonic presence embodied by “the machine”. There is no room in Kingsnorth’s theology for Christians who question his view that the Internet and the computers attached to it are inherently demonic. You’re either with Kingsnorth or you’re a materialist.

He eventually gets around to suggesting that his readers might consider responding to this dire state of affairs with one of two different forms of asceticism — asceticism at one of two extremes. At one extreme he suggests voluntary limits, and the acceptance of some inconvenience. At the other extreme, which he calls “raw asceticism”, is bombing the AI data centers. He doesn’t eschew the latter, but leaves the choice up to the reader. He never actually takes the option of bombing the data centers off the table. He even suggests that the more nuanced approach of self-denial and inconvenience may become rapidly untenable and that those who object to the AI zeitgeist may be forced into the more radical “raw asceticism”. Kingsnorth suggests that the more extreme option, which includes, in addition to bombing, completely unplugging from the world with “the Amish as your lodestones”, may become the only way forward for faithful Christians. (One is tempted to suggest that the Amish are unlikely candidates for getting on board with the bombing.)

If we set aside Kingsnorth’s strident (and hopefully hyperbolic) language about bombing data centers and pushing people off of mountains, he has, in noticeable ways, subtly adopted the assumptions of the broader culture by minimizing the implications, and the possibilities, of human agency. In Kingsnorth’s telling, technology is the primary mover in these events; it is the sentient being, acting on us of its own accord.

One of the fundamental mistakes made by catastrophists has always been to underestimate the dynamic effects of human agency. Failed predictions of catastrophe (e.g. the population bomb, global cooling, acid rain, global warming, CO2 poisoning) very often share in common a static analysis of human behavior. They rely on the assumption, often unstated, that notwithstanding the trends they identify, nothing about current human behavior will change, and catastrophe is therefore inevitable. (This kind of static analysis is also behind repeatedly failed predictions regarding how tax policies will affect tax receipts. When you raise taxes 10% you don’t collect 10% more in taxes. People adapt their behavior to the new tax rate reality.) Extrapolation of societal effects through means of static analysis is notoriously unreliable and hopelessly naive, when it is not actively malevolent.

Kingsnorth is not alone, of course, in his expectations of impending doom. He himself includes many examples of others who share his gloom. And I offer some additional recent examples below, ranging from predictions that all genuine human beauty will become a thing of the past, to the impossibility of ever again having fully human inter-personal relationships.

This kind of gloomy rhetoric is everywhere and thus easy to find. I could easily provide many other examples. Kingsnorth is no outlier, though he may be one of the more extreme.

In addition to the general problem of employing static analysis, which I mentioned above, many of the catastrophists would do themselves a favor by enlarging the set of voices they are taking their cues from. The press is entirely incentivized to make every utterance as sensational as possible. Their entire business model, after all, involves attention-getting. So they tend to concentrate their interviews around people who are willing to make the most outrageous claims, and wildest accusations.

The doom mongers would benefit from reading and listening to more of what might be called “AI realists”. The AI realists are less flashy and garner less of the spotlight, because their reasoned analysis tends to offer less sensationalism and more modest caution, combined sometimes with a pinch, even, of optimism. An example of an AI realist is someone like Erik J Larson, who has long challenged the grandiose claims being made regarding artificial general intelligence.

Others, like Meta’s chief AI scientist, are now openly saying what Larson has been insisting all along, which is that human level intelligence is never going to emerge merely by scaling current AI techniques.

There are even plentiful arguments against the fears of mass unemployment and economic catastrophe that are widely being peddled4. Marc Andreessen has offered one such argument, even if somewhat cynical, which is nevertheless also arguably realist in regard to our current marketplace dynamics.

The debates surrounding the kind of creative destruction wrought by new technologies have been going on for a long time. And every time the doomsayers have insisted that “this time is different”. This time, they say, the results will be apocalyptic. So far, at least, they have always been wrong. No one can reliably predict the future, of course, but until the catastrophists start employing a dynamic analysis that strongly accounts for human agency, I am not inclined to embrace their gloom.

None of what I have written so far should lead the reader to assume that this writer takes a Pollyanna view of technology or of AI. Any optimism or gloom I might tend toward is tempered, I hope, by a biblically informed understanding of human nature. And I want to suggest we would be wise to avoid the polar extremes of both exuberance and of despair. We should act with informed prudence, while exhibiting a more anti-fragile approach to living in the current moment.

“Self-pity is a pile of bricks on your chest, and your real friends help you heave it off.” - David Gelernter, “Drawing Life”

We should also temper our analysis with an honest assessment of both harm and benefits. I have written before about the risks of deception inherent in language models, and the curious effect that machines with linguistic ability have on human beings. I am no undiscriminating AI booster. But neither am I blind to the beneficial effects that this technology can have on human flourishing.

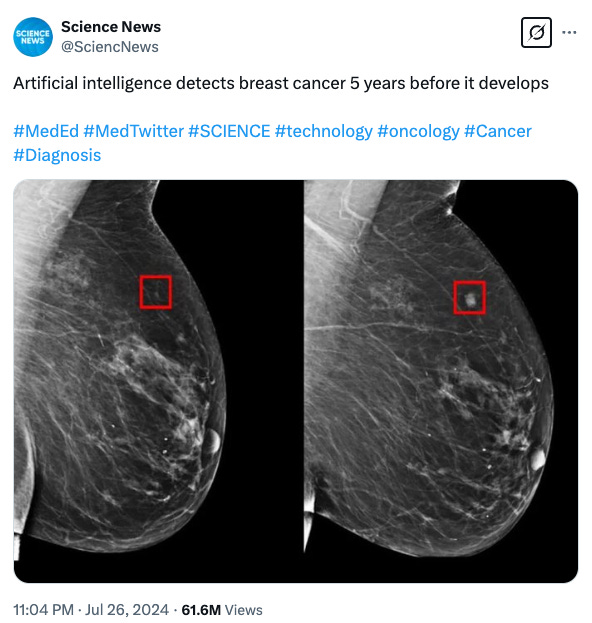

The reality is that the very same computational techniques being employed by language models, which are creeping out so many, are also being used in many other areas, in beneficial ways that most of us are entirely blind to. Everything from industrial safety to the longevity of appliances will be improved by AI. Medical diagnostics will improved. And AI is likely to improve, in some cases dramatically, the every day lives of those who suffer from physical handicaps.

So maybe some of us should take a deep breath and give all of this a little more thought.

Finally, I want to revisit something I mentioned earlier: we need to adopt a more anti-fragile response when responding to new technologies. There is more than a little hysteria within the Christian community, although AI hysteria is certainly not confined only to Christians. There is, after all, a very long history of catastrophizing advances taking place in tech well outside the Christian community.

I’m certainly not suggesting we should be blind to the damaging effects of specific applications of technology. I am on record arguing for a biblically informed framework as way to evaluate the moral basis for any particular technology. I am not blind to the negative impact of social media, for example, nor its malevolent use of intermittent rewards. I am entirely in agreement with the importance of voluntarily opting out of many different technologies, and so I sympathize especially with Paul Kingsnorth’s idea of the “cooked barbarian”. I am enthusiastic about the work and initiatives being pursued by Ruth Gaskovski and Peco, even if I would not be surprised to discover they don’t always agree with my take on things. They are doing virtuous and prudent things which are helping people, I have no doubt. I believe Jonathan Haidt’s work is extremely important. I am under no illusions about whether AI is sometimes being unethically applied. I am not an inveterate booster of technology. I entirely share David Gelernter’s concerns about the propensity of computers to bring out the worst in us.

The thing that should concern us is much less about the tech itself, and much more about the fallen men who wield it. The problem with tech is not tech, it’s us.

So I would love to see less hysteria and more intellectual rigor coming from the Christian community especially. More evidence of being substantively informed about technologies before raising alarms. Less belief in the omnipotence of tech itself, and firmer grounding in the fall of man.

Less despair and more hope. Less fragility and more manliness. Less victim and more hero.

A fundamental assumption of Judeo-Christian thought is that human agency is real, and therefore moral responsibility is real as well. Perhaps, then, rather than despair at advances being made in AI, we should lean into the reality of our own human agency and moral responsibility. We might really benefit by doing more manning up and less rushing to the fainting couches.

We were made for such a time as this. Panic in the face of temporal fears is not the way. We, of all people, ought to already know how all of this ends.

“…so that we may make a name for ourselves“ - Genesis 11:4

“Drawing Life”, David Gelernter

“let’s say too that the materialists are right. There is no Ahriman, no Antichrist, no self-organising technium, no supernatural realms breaking through into this one. This is all florid, poetic nonsense. We are not replacing ourselves. We are simply doing what we’ve always done: developing clever tools to aid us. The Internet is not alive; the Internet is simply us. What we are dealing with here is a computing problem…" This is, according to Kingsnorth, the “materialist” understanding of AI. This is placed in explicit contrast to what he conceives of as a spiritual view, which is that the Internet and its connected devices embody an intelligent, alien, supernatural being of some kind.

Great reflections on tech, with lots of important nuance that is often overlooked.

I think we are in a moment in history where the pendulum has swung away from rationality, especially (but not only) in our thinking around religion and spirituality, and so any effort to assert the importance of rationality, analysis, or language, is a hard sell, as it goes against the vibe.

Thanks for your thoughtful reflections Keith! "We should act with informed prudence, while exhibiting a more anti-fragile approach to living in the current moment." I concur with your point about thoughtful prudence when it comes to navigating issues around AI. I just mentioned to a friend yesterday that one of my greatest concerns with regard to AI is for the young generation, who may be tempted to use these tools before ever developing their own mental capacities to reason, research, read deeply, communicate clearly etc. While I may not fully agree with your take (I do think that AI advancements have a categorically different effect on us than previous technological inventions), I think you present a worthwhile, nuanced perspective.