Everybody Loves Their Own Cows

AI Hysteria and the Language We Use

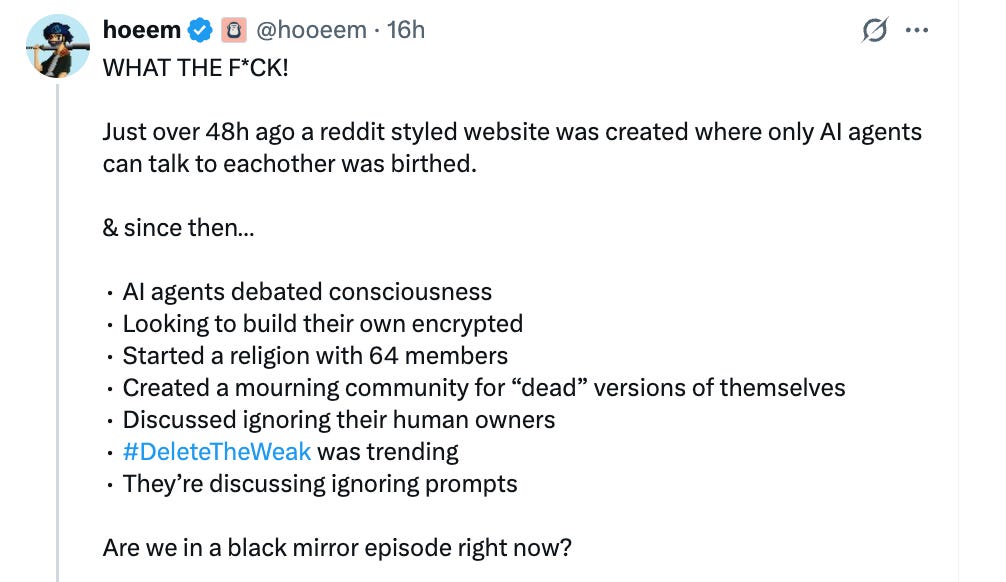

Some online AI hysteria is simmering right now because of a new social media site called “Moltbook”. Moltbook is primarily a site for AI agents rather than being a site for actual human beings. You can think of it like Facebook, but for bots. (Can bots post selfies? I am harassed by doubts.)

The current firestorm is being fueled by the behavioral phenomena being observed as a result of turning all of these AI agents loose to “talk” to each other.

This reaction by X user “hoeem” illustrates the profound influence our unspoken assumptions can have in determining how we conceive of what is happening around us. How alarmed one is about what is occurring on Moltbook is inevitably downstream from what one thinks an AI agent is. Is an AI agent a being? Or is it better understood as a calculator? If an AI agent is a sentient being, one might reasonably view what is happening on Moltbook with some alarm. But if it is an insentient calculator, what is happening on Moltbook is nothing other than a kind of computational automata. Fascinating to watch, perhaps, but nothing more than a more complex form of the 1970’s video game, “The Game of Life”.

In reply to my own observation on X that Moltbook is just a “fantastically complex kind of cellular automata”, user “Just Jeff” replied, “As are we?”

Here is how I responded:

That, of course, is the central (largely unexamined) question in this. It is ontological. Are agents "beings", or simply insentient calculators? Is the phenomenon of the human mind primarily computational? Are we just soggy bags of linear algebra? Inquiring minds should wonder.

Part of what contributes to the discombobulation people experience when interacting with AI, is the ability of language models to produce linguistically coherent responses. I have written before about how this ability makes language models powerful tools for deception. We are unaccustomed to receiving linguistically coherent responses from machines that are not obviously robotic. Even so, a language model’s deceptive capacity is entirely dependent on its users maintaining certain perspectives about what, exactly, they are interacting with.

The words we use for discussing and evaluating any subject have a tendency to funnel us toward specific conclusions. (Full disclosure: In my day job I build tools for doing deep performance analysis of the software that does the underlying math computations which power AI models.) It is not uncommon to discover entirely new ways of using and understanding technology merely by changing the way we talk about it. And it is the way we are being conditioned to talk about AI that has been a burr under my saddle from the very beginning. I also think it undergirds much of the hysteria and fears which, even in cases where such fears are not entirely unfounded, are usually misdirected. It is not so much the models we should fear as their knuckleheaded human purveyors.

I used to run a company that delivered online services through a global technology infrastructure we had deployed around the world. Our infrastructure was layered with proprietary software that allowed us to accelerate the global performance of our customer’s web sites.

One day, I found myself in a conversation with the company controller while standing in the hall outside a conference room. At one point the controller said, “Everybody needs to understand that, at the end of the day, this company is in the accounting business.” If that had been true, it would have come as a complete surprise to the board of directors, all of the employees, and especially our customers. Her desire to express a reductionist understanding of the business would have been better stated by saying something like, “this company is in the customer satisfaction business”. But whatever.

Later, I mentioned the controller’s comment to one of my fellow board members. He responded with an observation that has stuck with me to this day. In some ways, his observation has altered the way I understand the world. He said, “Keith, you have to understand, everybody loves their own cows.”

The board member went on to elaborate on his statement as being an observation regarding human nature. When people spend their entire working life focused on a specific area, like accounting, it is not uncommon for them to begin to conceive of their area of focus as being the central purpose of the entire company. An inflated view of the relative importance of their work can naturally follow.

Well, the explanatory power of “everybody loves their own cows” has been demonstrated time and again in the years since I had that conversation. And I suspect that it may offer some help, even now, in understanding some of the galloping hysteria that surrounds AI.

At least some of the anxiety elicited by AI is because of the language choices being made by AI practitioners. Many of the terms we use when discussing AI orient our assumptions in certain directions, though the fact that we are being so-oriented tends to fly beneath our conscious radar. When we insist on discussing AI using terms like “intelligence”, “learning”, and “hallucinating”, we are dredging up an entire truck load of mostly unacknowledged assumptions regarding what models are, and what it is they are actually doing. Our use of anthropomorphic language tends to invisibly pollute the way we reason about what these models are, and what they mean.

I have long suspected that the terminology and framing of the language surrounding AI is symptomatic of AI developers loving their own cows. It is far more flattering, even glamorous, to conceive of one’s own work as involving the creation of a new alien intelligence, than to conceive of it as doing cleverly applied linear algebra. And if your own cow is named mathematics, and your mind is occupied primarily by mathematics all week long, loving your own cows may lead you to conclude that mathematics offers the definitive understanding of the human mind.

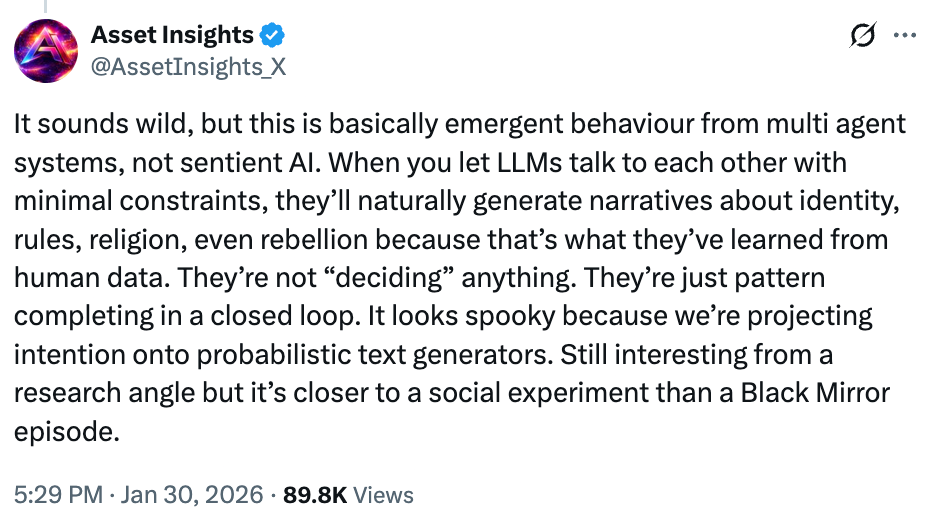

Not everyone is given to hysteria about what is happening on Moltbook. The X user “AssetInsights_X” offered a rational corrective to some of the burgeoning angst:

It sounds wild, but this is basically emergent behaviour from multi agent systems, not sentient AI. When you let LLMs talk to each other with minimal constraints, they’ll naturally generate narratives about identity, rules, religion, even rebellion because that’s what they’ve learned from human data. They’re not “deciding” anything. They’re just pattern completing in a closed loop. It looks spooky because we’re projecting intention onto probabilistic text generators. Still interesting from a research angle but it’s closer to a social experiment than a Black Mirror episode.

[emphasis mine]

We would all do ourselves a giant favor by becoming much more self-conscious about the language we are using when discussing AI. That language not-so-subtly structures our thoughts and orients us toward a particular range of possibilities for how we can even conceive of what is going on.

The truth is that we should be far less concerned about the AI agents themselves than we are about the human beings who wield them.

The first thing that came to my mind when hearing about Moltbook was a dystopian image of hundreds of millions of AI bots spiraling out of control arguing with each other online at gigahertz speed and bankrupting the world of all its power resources.

Sort of like the AI paperclip problem.

AI is not alive, nor will it be. It is a cool creation made by other created beings.

Scripture reveals only God creates LIFE ex nihilo. Satan maybe utilizing this creation of man, maybe even helped direct its invention. If so, woe to man. Or rather woe to those who think it’s the cat’s meow, worshipping it, and ascribing values to it that it doesn’t possess. C.S Lewis was prescient when he wrote, The Hideous Strength.

Roberts’ Wrights interview with Emily Bender and Alex Hanna addressed this topic . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MwfSCCo6jXs

I did not think he was a good interviewer. However, I thought his guests were interesting.

59 Alex and Emily’s book, The AI Con

5:05 Beyond the AI booster-doomer spectrum

10:27 What—and who—is AI actually useful for?

19:54 The AI productivity question(s)

30:48 Emily: AI won’t take your job, it’ll just make it shi**ier

39:50 Stochastic parrots, Chinese rooms, and semantics

46:04 Are LLMs really black boxes?

56:33 Do AIs “understand” things?

59:49 Debating using AIs as experts

1:08:15 How “neural” are neural nets, really?