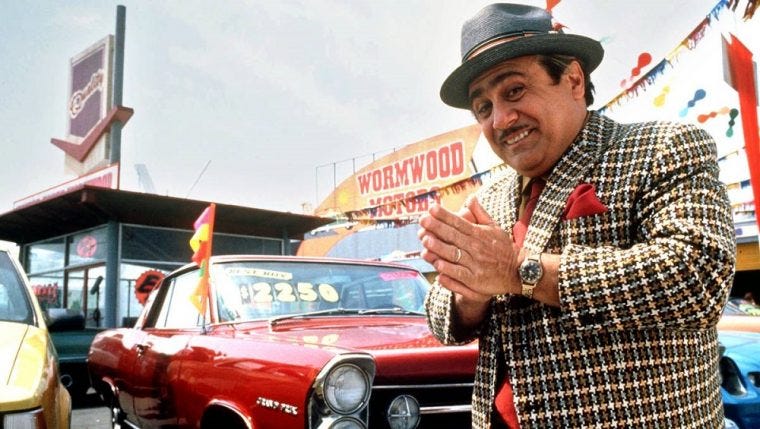

The Assumptive Close

Christian Nationalism's Detractors

Anyone who sat through a sales training in the 1980’s or 1990’s was probably schooled on the technique of the “assumptive close”. The assumptive close is a sales tactic that involves subtly manipulating a potential buyer into skipping over the question of whether he wants to buy your product, instead having him focus on just how many of your products he wants to buy. So rather than a sales person asking, “Would you like to place an order?”, using the assumptive close, sales people are trained to ask, “Would you like to buy only 2, or get the full discount by buying 6?” It’s called the “assumptive close” because the sales person is trained to nudge the buyer toward assuming that his decision to purchase has already been made. With the assumptive close, the decision to buy is simply assumed. Only how many the buyer is going to order is thus left to be decided.

This technique is actually somewhat effective. I’ve always suspected it works because the cognitive load of buyers in the throes of making a decision works against the inclination to step back from the decision-making process to methodically identify and analyze one’s own unexamined assumptions.

There is much hyperventilating on display right now over a relatively new booger man called “Christian Nationalism”. I confess I’m not entirely sure what is meant by that term. As far as I can tell - in the most generic sense - Christian Nationalism seems to be the belief that Christian insights into justice, anthropology, and morality should be reflected in civil and criminal law. Views on how to accomplish such a goal, and the aspirations for what form such laws might take, seem to vary as widely as the number of people who describe themselves as Christian Nationalists. My uncertainty of how Christian Nationalism is defined is also due to the term being so often used by people who only intend to emphasize that it should be associated with a sense of foreboding. Often, any substantive definition of Christian Nationalism itself is withheld. When the detractors of Christian Nationalism do provide a definition of the term, I find that their description differs markedly from those descriptions offered by self-identified Christian Nationalists. The main thing the detractors seem anxious to make clear to me is that I am expected to be in high dudgeon about Christian Nationalists. Exactly why I should be worked up, the detractors feel safe to assume, can be left to my own imagination.

It is the detractors’ reliance on vague and unarticulated fear which has left me harassed by a nagging suspicion: the detractors of Christian Nationalism seem to be no strangers to the concept of the “assumptive close”.

Now, the ambiguity which surrounds the meaning of “Christian Nationalism” causes me to refrain from actively writing in support of it. In this post, I neither affirm nor deny my belief in its validity and desirability. I just don’t know. But I have so consistently observed poor and, arguably, underhanded rhetorical tactics employed by its detractors, that I thought it might be worth dragging a few of the detractors’ assumptions out into the open - especially those assumptions which those same detractors tend to gloss over in their eagerness to “make the sale”.

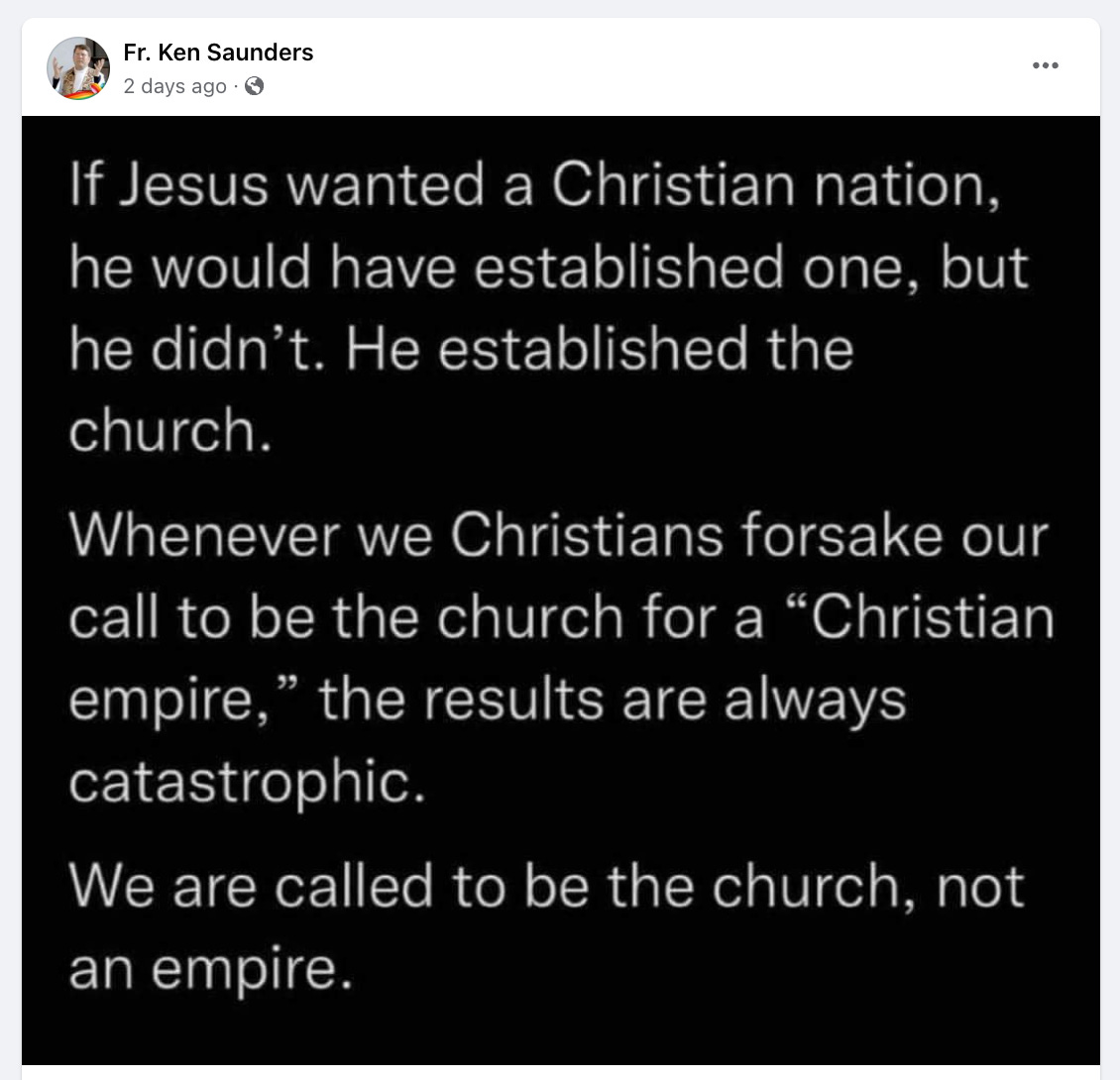

A few days ago I stumbled across an example of the kind of thing I’ve been talking about. One Fr. Ken Saunders posted his thoughts, as you see above, on Facebook, in order to publicize (one can only surmise) his rationale for objecting to Christian Nationalism. Fr. Saunders is apparently an Episcopal priest in the little town of Greeneville, Tennessee. Perhaps it is worth noting that on his profile page, and even on his personal profile photo, Fr. Saunders has adopted the rainbow flag as an adornment. That decision on his part is what a financial analyst would call a “leading indicator”. Poker players would call it a “tell”.

You may have, like myself, observed the unhappy history of neo-pagan antics being engaged in by the Episcopal church leadership over the last generation or so. Perhaps long ago you, like me, also stopped expecting to find intellectual or moral rigor emanating from that church’s pronouncements. But, sad to say, they are no less zealous, even if they have deteriorated to the point of becoming really dumb. More than once the modern Episcopal leadership has brought to my mind Flannery O’Connor’s observation that “ignorance is excusable when it is borne like a cross, but when it is wielded like an axe, and with moral indignation, then it becomes something else indeed.”

I don’t pick on Fr. Saunders because he represents a key player in the organized resistance to the booger man of Christian Nationalism. For all I know, his influence ends at the city limits of Greeneville, Tennessee. I only bring him up because his post happened to come across my personal radar, and because I think it neatly illustrates the kind of thing I have been trying to describe.

Like many clergymen, Fr. Saunders makes three points in his little Facebook “homily”. Let us unpack them in turn.

1. If Jesus wanted a Christian nation, he would have established one, but he didn’t. He established the church.

One of the unexamined assumptions in this statement is that Jesus established everything he wanted when he established the church. This is akin to saying that anything Christians establish beyond the church is not something Jesus wanted. You can see the silliness of this idea by replacing the words “Christian nation” with other things that have been established in the interim which were not things Jesus himself established.

“If Jesus wanted a Christian orphanage, he would have established one…”

“If Jesus wanted a Christian seminary, he would have established one…”

“If Jesus wanted a Christian hospital, he would have established one…”

Hopefully you get the point. Fr. Saunders’ audience is supposed to gloss over his unstated assumption that anything downstream from the establishment of the church is ipso facto something Jesus didn’t want. This line of reasoning becomes silly once you make it explicit and give it even a moment of thought. It is an example of what someone has called a “deepity” - a superficial statement that only seems profound but on close examination is frivolous or merely wrong.

That Fr. Saunders makes a silly argument is not, of course, a point in favor of Christian Nationalism. I only mean to observe that Christ’s establishment of the church does not itself actually tell us anything at all about whether Christian Nationalism is a worthy pursuit.

2. Whenever we Christians forsake our call to be the church for a “Christian empire,” the results are always catastrophic.

Several things are happening here in Fr. Saunders’ second point. First, there is the implied assumption that Christians cannot walk and chew gum at the same time. We simply cannot “be the church”, Fr. Saunders encourages us to silently assume, while also applying our Christian insights to other areas of our lives. Notice too, that Fr. Saunders has silently replaced “Christian nation” with “Christian empire” - without comment. Notice also the scare quotes that are employed. Perhaps Fr. Saunders himself knows of someone who is advocating for Christian empire. I personally do not. But I will offer that the only self-described Christian Nationalists I have read go out of their way to eschew any notion of “empire”. Home and hearth seems to be much more of their concern. I gather from the unremarked substitution of “empire” made by Fr. Saunders that I am supposed to conjure up my own imaginary pictures of military adventurism into foreign lands under banners bearing crosses. Perhaps even with a large dollop of the Crusades. Which dark forces, exactly, are advocating in favor of empire building is something that is left to the reader’s imagination. We are simply to assume their existence.

3. We are called to be the church, not an empire.

This is an example of another deepity. Being “the church” is simply not mutually exclusive with being other things we are also called to be. We are called to be fathers, mothers, husbands, and wives. There are many things we are “called to be” besides being the church. We need not choose between “being the church” and being other good things. Again, I would not argue in favor of “empire” in any case, but the unstated assumption here is that we cannot “be the church” concurrently with pursuing anything else at all. This flies in the face of both common sense and human experience.

More General Observations

Stepping back from Fr. Saunders’ objections to Christian Nationalism, there are some other themes among the detractors that I think are worth mentioning.

Often seen among the detractors of Christian Nationalism is the typically unspoken premise that the insights of Christian truth, to the extent they can even be known, are primarily operable for the psycho-moral rehabilitation of the individual. They are not applicable to the fields of public policy and law. Or, if those insights are applicable and knowable, Christians should nevertheless refrain from using the means at their disposal to advocate for them, or ever to enact them. None of the detractors I have been able to read has been eager to put it quite as baldly as I just did. But from my vantage point, that is the unavoidable presupposition which serves as the launching pad for much of what constitutes their reasoning. As a result, any practical civil application of the insights provided by, say, Christian anthropology, is a priori placed out of bounds in matters of law and politics. In some cases, merely even advocating for the application of Christian principles in policy and law is treated by detractors as bordering on idolatry.

Does the Bible speak to the questions of public life in any way that is apprehendable by Christians, or that it is virtuous for them to advance in the public square? The Christian Nationalism detractors seem to say, “No”. But I would like to ask the question from a different angle. Why is advocating for just laws, and taking part in enacting them, not by definition an act of love toward one’s neighbors? Detractors often say that Christians should confine their concerns to loving mercy, acting justly, and walking humbly with their God. Ok. Is it an act of love, or of indifference, for someone to passively stand idle in the face of unjust laws, when there are means at his disposal for changing such laws? If the German Christian community, during world war two, had broadly organized against the Holocaust, would that not have counted as love? Or would it have merely been more power-seeking by power-hungry Christians? Whatever the merits of Christian Nationalism might be, about which I make no claims, many detractors of Christian Nationalism exhibit a pinched and impoverished understanding of what it means to love one’s neighbor.

The other attitude, common among detractors of Christian Nationalism, is an eager and abject passivity in the face of government’s usurpation of the prerogatives and responsibilities of the church. If even the events of the Covid19 pandemic didn’t make the government’s usurpations obvious, then I can’t help you. Months, even years, went by during the pandemic with Christians being forbidden by their governments from gathering together. Communion and baptism, for many believers, faded into the past. But even apart from events during the pandemic, the biblical and historical concerns of the church, ranging from care for the poor to the sanctioning of marriage, has long been usurped by the machinations of government. Many of the detractors of Christian Nationalism have been the most vocal advocates and cheerleaders for vaccine mandates, church closures, enforced distancing, and government control over almost all resources intended for the poor. Far from decrying such usurpations, many of the critics of Christian Nationalism have been actively complicit. Thus do their criticisms of Christian Nationalism fall on deaf ears where I am concerned.

I honestly have no idea what I think of Christian Nationalism on the merits. I am averse to any view that offers utopian visions about the possibilities that adhere within the context of a fallen world. I’m not saying that Christian Nationalists are making such offers, only that people sometimes do overshoot their intended target. But whatever is right or wrong about Christian Nationalism, the arguments and sales tactics of its detractors emit a distinctly unpleasant odor. Such detractors will not be closing a sale with me.

Being old school, I can see his Worldview bleeding out all over this article. He is living out his doctrinal WV in print.

The Democratic Party calls a person who is a Christian and votes Republican a Christian Nationalist who is also dangerous. It’s simply propaganda. Next, the Democrats will say the Bible is what makes Christians dangerous so bibles will have to go. I think that is already happening.