The Allure of Shiny Baubles

Artificial Intelligence, Cognitive Passivity, and Social Combustibility

The human act of articulation enriches understanding, not just for the hearer, but also for the one who is doing the work of articulation. Going through the process of putting something into words forces our thought process through a nozzle that imposes coherence and an increase of logical rigor. Putting our thoughts into words not only puts the hearer’s understanding on firmer footing, but actually strengthens the speaker’s own grasp of the subject. This is one reason I believe widespread use of AI language models could have the unintended side-effect of diminishing the sum total of human understanding in the world.

I learned this effect of articulation through experience, when I and my colleagues observed that when we encountered a complicated or thorny bug in our code, surprisingly often, if we put the problem we were having into words, the mere act of articulation made the solution to our problem obvious. The logical structure imposed by putting things into words makes us think more cogently about the problem we are facing.

I noticed this again, sometime later when doing (never completed) graduate work. The greater emphasis placed on writing, by the master’s program I was in, resulted in a more thorough…er…mastery of the subject matter we were grappling with.

Recently I’ve had conversations with various teachers at both the high school and college levels, and the effect of AI language models has been something akin to a large grenade being thrown into the process of education. Responses to AI, among the admittedly small circle of teachers with whom I have discussed it, have ranged from outright bans on AI-generated writing, to seeking ways to accommodate AI as long as proper attribution is given. I have no idea how the mechanics of an outright ban can be effectively enforced. I am entirely sympathetic with the plight of educators in a world of large language models. But I cannot help but suspect that allowing any use of language models will invariably mean the acceptance of some reduction of actual learning on the part of the student.

I don’t know how to avoid the conclusion that widespread employment of AI language models will have the effect of reducing the prevalence of human-generated content. In such a case, it will have a diminishing effect on the depth of subject mastery by humans, along with a corresponding reduction in coherent thinking across many different disciplines. A thoughtful person has to at least wonder whether the cumulative cognitive effects of language models on human expertise will be analogous to the effect that widespread porn consumption is suspected of having on fertility in the West.

By relieving students and workers of the need to think well enough about something to articulate it themselves, language models reduce the benefits and logical rigor that comes from putting things into our own words. In either case, of course, whether by the use of AI models, or by articulating things for ourselves, we will have gained the “weight” of possessing information on a given subject. But there’s a qualitative difference between gaining weight by being spoon-fed carbs, and gaining weight by lifting at the gym. Fat and muscle are not the same.

Our human attraction to the shiny baubles of technology can lull us into unwariness. The passivity induced by the conveniences that AI affords can make us blind to the longterm ill effects of outsourcing our own mental initiative. The pleasure we take in clever inventions can anesthetize us to the pain of perceiving our creeping cognitive passivity. If an unreflective skepticism toward all new technology is unwise, surely so is an unexamined enthusiasm. Discernment inevitably involves hard work, and it will almost certainly require a conscious choice to sometimes refuse the path of cognitive convenience.

Perhaps even more puzzling (and dangerous) for us though, in our current moment, is our understandable tendency to believe our own eyes and ears. We are living through an amazing transition during which forms of evidence, which in the past could only have represented actual human activity, can now be entirely fabricated. Video, audio, pictures, voice recordings, handwriting, and the written word, things that within this very generation, could only have been produced by human beings, can now be conjured out of thin air. I’m afraid that ours is the generation that will have to recalibrate all of its assumptions regarding the assumed validity of digital evidence. AI’s ability to mimic the products of human activity makes the risk of human deception very high.

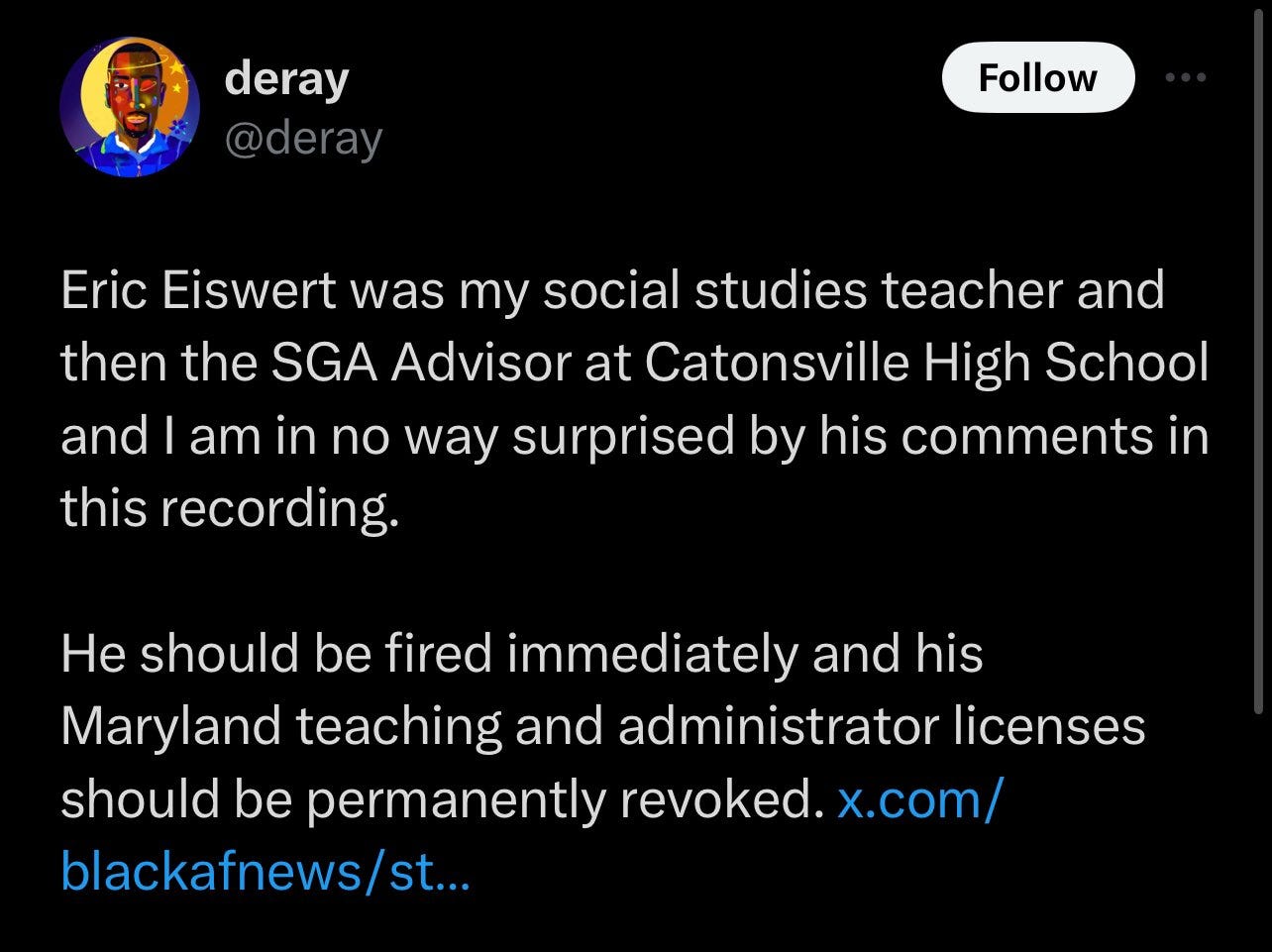

Just this week, a former athletic director of a Baltimore, Maryland high school was arrested and charged with fabricating evidence of racism against one of the school district’s principals.

Baltimore County Police arrested Pikesville High School’s former athletic director Thursday morning and charged him with crimes related to the alleged use of artificial intelligence to impersonate Principal Eric Eiswert, leading the public to believe Eiswert made racist and antisemitic comments behind closed doors.

There are AI services to which you can provide a short voice recording, along with your own original script, and these services will produce an authentic sounding audio recording of your script using the voice print from the recording you provide. In this case, the athletic director uploaded an innocuous recording of the principal’s voice and had the AI, quite literally, put racist and anti-semitic words in the principal’s mouth. The recording may have been fake, but the pain and social upheaval was very real. The principal was suspended and made the target of vitriol by people in his local community and beyond.

It is a matter of physical survival for biological creatures to be able to generally assume the veracity of what they see and hear. So recalibrating our natural human tendency to react to another person’s voice, or watch their image on a video, and no longer believe they really said or did those things, is going to be a difficult transition. We are uniquely susceptible to deception in this way. And unless the detection of AI-generated content is foolproof, and the workings of detection technologies are made comprehensible to the average person who might, say, sit on a jury, we are going to be in for a difficult period of injustice, and of framing the innocent. Either that, or we will have to reject digital evidence (e.g. security camera footage) as a matter of principle, since it will have become something we can no longer confidently substantiate as a reliable vehicle for discerning truth. We are unfortunately entering into a period where miscarriages of justice will probably become more common, with all the associated societal upheaval. The unfortunate Baltimore county school principal is probably just the tip of the iceberg.

It seems to me that the path of wisdom would tell us that we should be far more skeptical of everything we come across online. This is especially true whenever something neatly foments a controversy regarding which the social and political stakes are high. We are likely to see all manner of shenanigans during the current election cycle. We should expect the emergence of AI-fabricated digital evidence about everything from secretly harbored racism, to sexual infidelity, to audio “recordings” of politically damaging things a political candidate supposedly said in private. Our first reaction should be to ask, “Where did this really come from?”

It’s one thing to be lied to through the use of fabricated evidence. But it’s a whole different level of stupid to be so naive as to be complicit in one’s own deception.

“We know they are lying. They know they are lying. They know that we know they are lying. We know that they know that we know they are lying. And still they continue to lie.” - Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

I heard a lecture by Professor Scott Oliphant ( I believe this was it: https://www.sermonaudio.com/sermoninfo.asp?SID=99106132020520 )

wherein he said as of last year he no longer requires his students to write a paper at the end of term. The reason being that if he did, no one would pass his classes anymore. They can't put words together to make a premise or argument. They simply cannot do it. The last time he required it he said the highest grade he gave was a B, but it should have been a D. He was worried about the human mind being able to even understand God and the gospel as it requires a certain degree of contemplation which is going out the window as distractions decrease humans abilities to focus on one item long enough to find a solution. (You can Google it...) He decries how students will pull out a phone and start thumbing through it, even when he as their professor is having a one on one conversation with them!

My own way of explaining the good we derive from putting into words what we are thinking is that our minds are like a washing machine full of clothes. ( the old fashioned washing machines that you can open the lid and add items while it agitates.) You look in it, and see the clothes all twisted, surfacing and disappearing, amidst the foam. You can't really find, or know, what has been thrown in there because it is a squirrelly mess, but telling another person your thoughts, (or putting them down on paper) is akin to when you take the tangled mess out, and pin 'em up on the clothesline. Then you can recognize at a glance what you have, and what you are missing. "Where is the match to that sock! etc.