Mindworms

Getting stuck on a mental framing

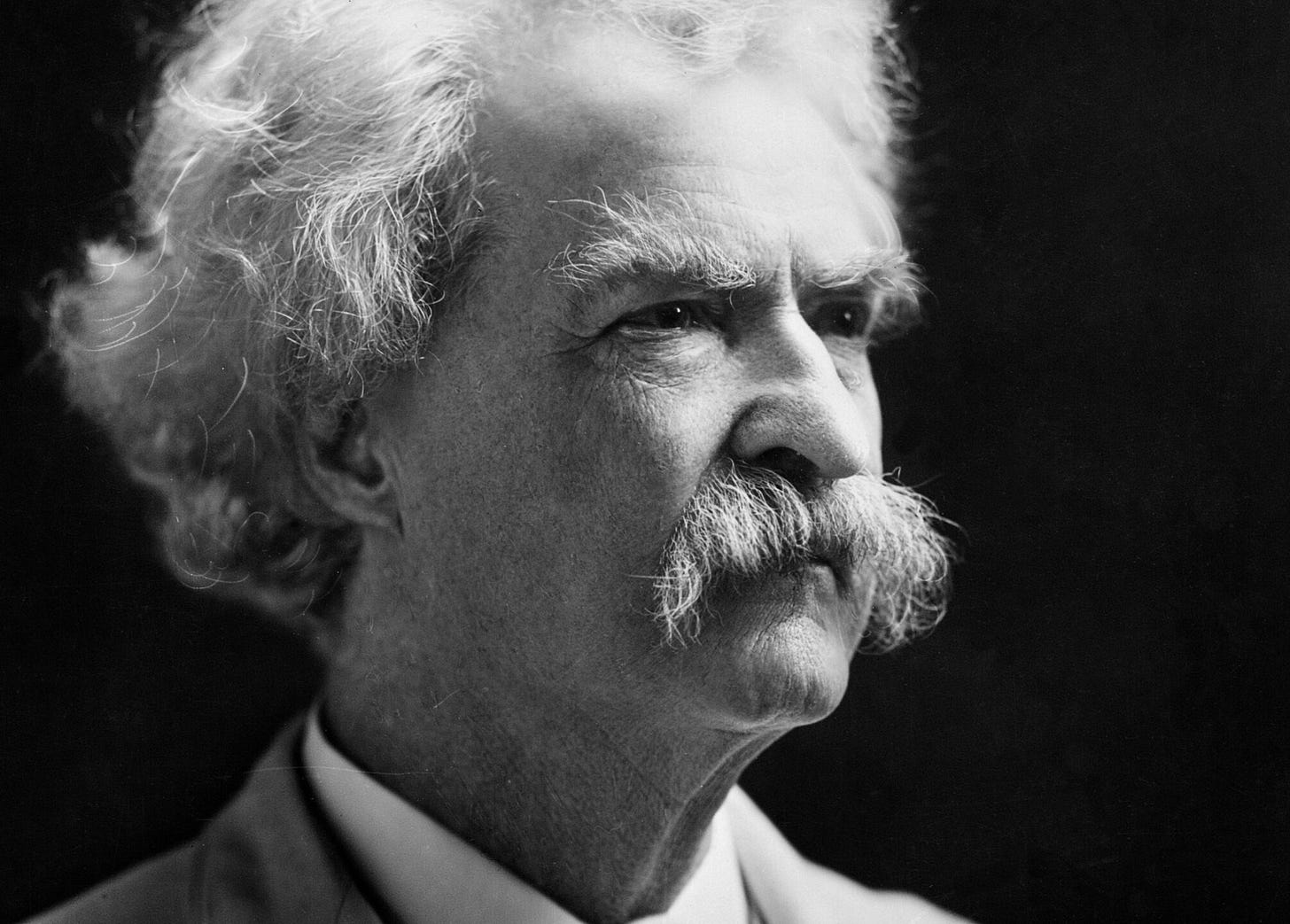

I have always loved the humorous essays of Mark Twain. I have two volumes of them on my bookshelf. Some of them are laugh-out-loud funny. His essay, Curing a Cold, recounts his effort to try every possible remedy to get rid of his cold. Acting on the axiom “starve a cold and feed a fever”, and having both cold and fever, he starved himself for a while before proceeding to an all-you-can-eat restaurant where he ate until he could hold no more.

Twain left the restaurant, stuffed to the gills, whereupon he encountered a “bosom friend” who told him that “a quart of salt water, taken warm, would come as near curing a cold as anything in the world.”

Twain writes:

“I hardly thought I had room for it, but I tried it anyhow. The result was surprising…I believe I threw up my immortal soul.”

In another essay, an excerpt from his book The Innocents Abroad, entitled Guying the Guides, he recounts touring Europe with a friend, with whom he made it a practice to hire tour guides for the expressed purpose of playing pranks on them. I used to read this essay aloud to my children at the dinner table, affecting the accent of the unfortunate guide. The children would laugh until they couldn’t breathe.

Describing this sight-seeing trip to Europe, in which Twain was continually being shown the works of Michelangelo, Twain writes:

I used to worship the mighty genius of Michelangelo - that man who was great in poetry, painting, sculpture, architecture - great in everything he undertook. But I do not want Michelangelo for breakfast - for luncheon - for dinner - for tea - for supper - for between meals. I like a change occasionally…I never felt so fervently thankful, so soothed, so tranquil, so filled with a blessed peace, as I did yesterday when I learned that Michelangelo was dead.

Twain and his friend proceeded to hire a sight-seeing guide whom they used for their personal amusement, continually asking him if the great personage from European history, being excitedly expounded upon by the guide at that moment, was dead.

They criticized the guide for showing them a 3000 year-old Egyptian mummy instead of “a fresh corpse”. Upon being shown documents handwritten by Christopher Columbus, instead of being appropriately awestruck at seeing a relic of “ze great Christopher Colombo”, they criticized the quality of…the handwriting, insisting on being shown something with better penmanship.

“Why, I have seen boys in America only fourteen years old that could write better than that.”

“But zis is ze great Christo--”

“I don’t care who it is. It’s the worst writing I ever saw. Now you mustn’t think you can impose on us because we are strangers. We are not fools by a good deal. If you have got any specimens of penmanship of real merit, trot them out! - and if you haven’t, drive on!”

Thus Twain and his friend spent days pretending to be complete idiots, just for the amusement of observing their guide’s reaction.

One of Twain’s funniest essays dealt with the phenomenon of earworms. An earworm, for anyone who happens to be unfamiliar, is that phenomenon which sometimes occurs when a person gets a catchy jingle or song stuck in his head and can’t seem to get rid of it. The song, or jingle, keeps playing back in his mind, over and over, until it becomes a complete annoyance. Twain’s famous essay Punch Brothers Punch is a hilarious recounting of his own experience with this phenomenon.

Lately, I have come to suspect that the earworm phenomenon is not confined only to jingles and songs. It seems also to appear in the realm of ideas. Or, at least, it occurs in the way certain ideas are framed. There are certain mental reasoning frameworks that seem able to entrench themselves to such a degree that it becomes nearly impossible for a person to dislodge them.

Let us call this phenomenon a mindworm.

Mindworms, in this telling, are not merely specific ideas, but more like unrecognized framings for how one even thinks about ideas.

To illustrate, perhaps the following example will help.

It is not always necessary to reduce calories in order to lose weight. Sometimes weight can be lost merely by changing the kind of calories one consumes. Individual results vary, of course. But it is simply not the case that losing weight always requires reducing calories.

But for some people, this is impossibly hard to…um…digest. They seem incapable of shifting the mental frame for how they reason about calories. That there might be kinds of calories; that weight loss may be a function of, not only calorie quantity but of calorie kind, is something that just doesn’t click. It isn’t that such a person can’t understand the words you’re saying, it’s that such understanding does not penetrate and shift the way they frame and reason about their conception of it all.

Thus, a mindworm, as I am using the term here, is the mental framing equivalent of an earworm. A mental structure for reasoning about some subject where the mental structure may not be entirely conscious. But the mental framing gets kind of stuck in one’s head, thereafter serving as gatekeeper for what is able to penetrate and update said mental framing.

More specifically, I am describing a kind of reasoning framework that inhibits any modifications to itself.

I am not here referring to close-mindedness in a willful sense. I am definitely not referring to intellect. But, rather, I am trying to describe a conceptual model, a way of thinking about some subject, which gets so stuck in one’s head that it resists any attempt to ever be modified. I am not simply referring to something like certitude. Certitude can be volitional and conscious. What I am describing is something more akin to write-once-read-many data storage systems, except in the realm of cognition. There are certain mental frameworks which, having taken up residence, prevent any updates to themselves. New information can be internalized. But it will be processed according to the mental framework which prevents its own modification. Thus you are able to learn new things, but you are not able to learn new ways of reasoning about those things.

After writing the above, in some of my reading I ran across the concept of cognitive entrenchment. It seems close to what I have been trying to describe. Grok describes cognitive entrenchment as “highly stable mental schemas that resist change”.

The more established the framework becomes, the harder it is to adapt — experts literally get “stuck” in their conceptual grooves.

I have actually had conversations of late that went something along the lines of what you will read below. The subject matter in this example is contrived, but the mindworm-effect it illustrates is true in all particulars:

Friend: Anything named “Fred” is a horse.

Me: What if something named “Fred” is not actually a horse?

Friend: Anything named “Fred” is definitionally a horse.

Me: Well, I suspect a cow named “Fred” would not actually be a horse.

Friend: Anything named “Fred” is a horse.

It is my growing conviction that some forms of systematic theology affect people like unusually persistent mindworms.

Peter Kreeft is great for going against this stuck in a rut. Look for his "Forty Reasons I am Catholic" where he uses many different mental approaches to look at faith.