Impervious

A Tale of Two Attempted Murders

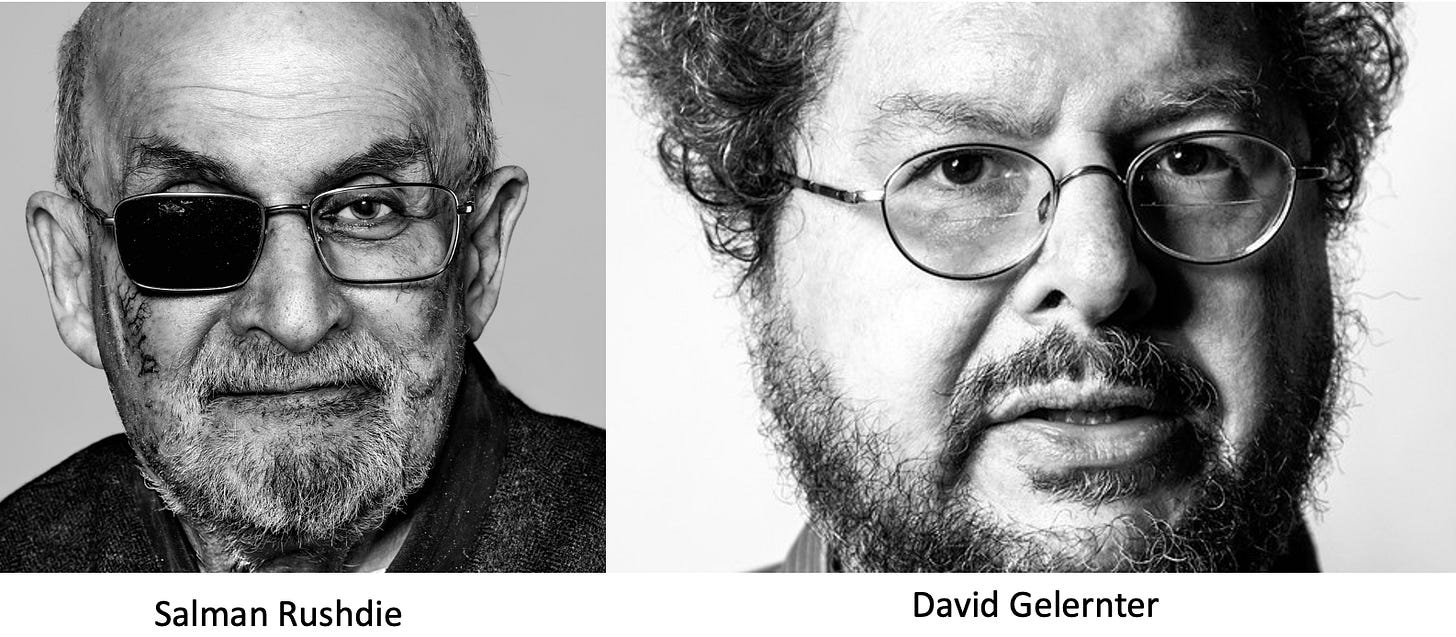

On August 12, 2022, author Salman Rushdie was stabbed nearly to death while he was giving a speech at the Chautauqua Institution in upstate New York. As he spoke, a man dressed in black came running down the aisle, leaped onto the podium, and began wildly stabbing Mr. Rushdie as the crowd looked on in shock. Mr. Rushdie is alive today because of the intervention of the onlookers, the work of medical personnel, and the love of his wife. But he now lives his life with permanent scars - both physical and emotional - and is blind in one eye.

Almost thirty years prior to the attempted murder at Chautauqua, David Gelernter, at the time a relatively obscure professor of computer science at Yale, opened a package delivered to him through the mail and was blown up by a bomb the package contained. He survived the attempted murder by the Unabomber and, like Mr. Rushdie, now lives with the permanent scars.

Both Rushdie and and Gelernter are writers and, as writers are prone to do, they have each produced a written record of their respective brushes with death. The similarly slim volumes produced by each of them contain their respective reflections on what they think it all meant. Rushdie’s book was released this past month, less than two years after the event, and is entitled Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder. Gelernter published his recollections in 1997, four years after the attempt on his own life. Gelernter’s book is called Drawing Life: Surviving the Unabomber.

It is not hard to feel sympathy for someone who has been very nearly murdered. Both Rushdie and and Gelernter came out of their experience with an acute appreciation for their families and for the love they share with them. Both men credit their wives with being central to their recovery. This will be familiar ground for any man who has come close to dying, only to unexpectedly survive. Some years ago I had my own near miss with death, and I had a very similar reaction. I wrote at the time:

“Comforted back to life. That's what has happened to me. At every step along the way, my wife has planted herself beside me - soothing me, reassuring me, kissing me, caring for me...comforting me. And often while I'm out of my head on drugs. Catastrophic health issues are a challenge on any basis, but they are insidious in the way they encourage you to despair. My wife is having none of it. She has lifted my spirits more times than I can count and has, using her vast reservoirs of faith, calmly and determinedly reassured me until I have had time for the pain to subside and to come to my senses. It would be impossible to overstate how central she has been to my recovery. She has loved me in the hard places. I adore her.”

In my own experience, nothing is more conducive of despair and exhaustion than relentless pain. And despair is one of the themes both Rushdie and Gelernter visit as they each describe their individual recoveries.

At the time of the attack on Rushdie, his children were already grown - Rushdie was in his 70’s when he was attacked. He writes with a palpable sincerity about his love for his children. The unambiguous love he expresses for his wife and his children serves as a helpful reminder to the reader of Rushdie’s humanity. I say it is “helpful” because it would be easy to conclude from the other parts of his book that he is generally oblivious, and impervious to learning. More about this later on.

By contrast, Gelernter had young children still at home at the time of his own attack, and he spends some of his time reflecting on how his injuries and resulting handicaps have altered his relationship with his little boys.

“I am overwhelmed one morning with a sense of tragedy as I pass my older boy’s bedroom and realize how I used to know all the junk in every corner of it, and spend time in there every day, and nowadays never go in; it is foreign territory to me. Stifling tragedy — for a while I can’t even move.”

But Gelernter doesn’t leave it there because he pushes hard against the allure of self-pity. “Self-pity”, he writes, “is a pile of bricks on your chest, and your real friends help you heave it off.”

Gelernter, in some ways, reinvents his fatherly presence in his young sons’ lives.

“I hadn’t seen my boys, who had just turned three and six, since the morning of the explosion. I had got the six-year-old a softball and his first baseball mitt for his birthday, and had been looking forward to the first time we would go out together and toss a ball around. What bothered me most in the hospital was that I would never be able to do that. It still bothers me acutely. But it is possible I gained more than I lost as a father. I never had the slightest doubt that fatherhood was my most important line of work, but nowadays each of their birthdays marks another year I have succeeded in being with them and doing what I can for them, and each year is an important victory…In time I invented a new game to replace baseball for me and my boys, now six and nine, called legitimate ball; the older player (the “dad”) drop-kicks a kickball in a high, tight arc and calls it in the air: You get 900 points for catching a “legitimate” kick, a quarter million for snaring an off-course “quasi-legitimate” kick and 81 trillion if you catch an “illegitimate,” which is ridiculously off course and usually lands on the roof…The goal of the game is to remember how many points you have. For nine-year-old players the goal is also to add up your score correctly. The scoring is complicated by the famous “free points” rule, which stipulates that the “dad” is allowed to hand out extra points to any player who needs cheering up; but when one fielder has been awarded a few million extra for cause (because he almost made a great catch, for example, or the ball bumped his nose), it often develops that the other fielder needs cheering up too. So the scores in legitimate ball can be substantial.”

This kind of good cheer infuses Gelernter’s writing and the reader will often find himself laughing out loud, alternating with weeping, as Gelernter grapples with his difficulties.

Rushdie’s memoir is never funny but, of course, it doesn’t have to be. There are a couple of places he tries unsuccessfully to incorporate humor, in both cases weirdly having to do with male genitalia. But it falls flat and comes across as more adolescent and mildly creepy than funny. I suspect Gelernter’s contrasting ability to make his reader laugh out loud is symptomatic of his much broader engagement with the moral and philosophical questions implicated by his experience. Only the truth, as they say, is funny.

Rushdie presents himself as an urbane, cosmopolitan, artsy intellectual. Indeed, he goes out of his way to leave the reader with that impression. But I nevertheless frequently found myself wincing at Rushdie’s cultural and intellectual obliviousness. His writing manifests a worldview that is both narrow and seemingly impervious. His ability to learn from tragedy seems to be circumscribed by prejudicial commitments to every trendy progressive shibboleth. His self-disclosure is almost a caricature of the self-satisfied, insular urban progressives who routinely inhabit the media.

For starters, Rushdie really seems to have a burr in his saddle about white people. He wrote at some length about his idea for a novel which seemed to be mostly a cry of rage against white people. He imagined a novel about someone named “Henry White” who is thoughtlessly happy, and the very thoughtlessness that characterized Henry meant that he must also be racially white.

“I thought, he can’t possibly be a person of color if he’s happy in that way. He had to be white…However, he did not think of himself as white, because white was the color of people who didn’t think it was important to think about their color, because they were just people; color was for other people to think about, people who weren’t just people…I wanted to do terrible things to Henry in my story: I wanted his parents to die, his fortune to be lost…I wanted him to be half killed in the Lisbon earthquake…I wanted him to be smashed out of the armor his whiteness had given him and to look at the world through nonwhite eyes.”

Perhaps you can see why I wince at this calculated disclosure of his own weird racial animus. It is oddly tone-deaf and out of place given the ostensible subject matter of his memoir. But his book is pollinated throughout with these kinds of sour little pockets of progressive groupthink. It makes me suspect that he is possessed by some unhappy neediness to check all of the required progressive boxes for holding right opinions - perhaps to maintain his membership in progressive social circles? Hard to know for sure. But he goes on to also inveigh against gun rights, the overturning of Roe, and religion in general. This dog’s breakfast of doctrinaire progressive hot buttons, scattered throughout, ruins what could have been a sympathetic account of Rushdie’s experience. Thus reading Knife is a bit like biting into a delicious cheesesteak, only to discover it has been sprinkled with moth balls.

And no recitation of progressive opinions would be complete without also taking a swipe at Donald Trump, which Rushdie does at least twice in his book. In one case he provides the reader with a helpful list of people who, Rushdie perceives, should “regret their lives”. The list includes the genocidal Adolf Eichmann, the sexual abuser Harvey Weinstein, and…Donald Trump. When a writer explicitly places Donald Trump on a similar moral plane as Adolf Eichmann, one of the true murderous monsters of world history, you can be sure that something other than empiricism or rationality is animating such a writer.

Throughout Rushdie’s reflections, he engages in considerable chest-beating regarding his lack of belief in anything religious. He wears his atheism as a badge of honor. And he goes out of his way, in the penultimate chapter of his book, to insist that nothing about having nearly been murdered implicates anything about his prior understanding of the world around him, or even whether his own lack of faith might warrant a second look.

“I have no need of commandments, popes, or god-men of any sort to hand down my morals to me. I have my own ethical sense, thank you very much. God did not hand down morality to us. We created God to embody our moral instincts.”

(Italics mine)

Note the insistent petulance, and even the unmistakable whiff of bitterness. In addition to merely protesting too much, one senses that Rushdie has embraced the original temptation offered in the garden of Eden: “Ye shall be as gods.”

By contrast, Gelernter’s reaction to his own attack, and the media’s moral equivocation in the aftermath, drove him to energetically engage and question many of his prior assumptions:

“But my experience…was so eye opening, it forced me to rethink everything I knew about American society.”

Gelernter’s book recounts not only having been nearly murdered, but what he discovered about the larger world as a result. By contrast, Rushdie takes great pains to make sure the reader knows the attempt on his life gave him no food for thought. None whatsoever. Bupkis. Because he already had all the right thoughts, you see, and “thank you very much”.

Such imperviousness is a breathtaking thing to behold.

From Salman Rushdie’s book you will learn a great deal about…Salman Rushdie. From David Gelernter’s book, you will learn a great deal about meaning, purpose, human nature, and justice. You will also belly laugh and weep by turns before ultimately being reminded of the most important things in the world.

Choose your reading wisely.

“To suffer longing and loss makes you not a victim but a human being.” - David Gelernter, Drawing Life