Free Hay

Eighteen years ago, I was an inconsequential speaker in one of the smaller side rooms at the annual InfoWorld confab for computer geeks. I don’t even remember what I talked about, but that happened to be the same year Bill Joy wrote his controversial essay “Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us”. The controversy surrounding Joy’s essay related to his view that self-replicating technology would eventually run out of control and was prone to wiping out humanity itself.

In one of the larger, more consequential venues of that InfoWorld conference, Bill Joy was there speaking about his recent essay. I was less worried than Joy about the threat posed by replication, but I was very much concerned with the prescription he was proposing. Joy believed the situation sufficiently dire that government should forcibly take the relevant technologies out of the hands of the public.

Here’s a sampling of things in Joy’s article I found creepy at the time:

“We have, as a bedrock value in our society, long agreed on the value of open access to information, and recognize the problems that arise with attempts to restrict access to and development of knowledge...But despite the strong historical precedents, if open access to and unlimited development of knowledge henceforth puts us all in clear danger of extinction, then common sense demands that we reexamine even these basic, long-held beliefs...Ideas can't be put back in a box; unlike uranium or plutonium, they don't need to be mined and refined, and they can be freely copied. Once they are out, they are out...The GNR [genetic/nanotech/replication] technologies do not divide clearly into commercial and military uses; given their potential in the market, it's hard to imagine pursuing them only in national laboratories. With their widespread commercial pursuit, enforcing relinquishment will require a verification regime similar to that for biological weapons, but on an unprecedented scale.“

Joy was essentially arguing that commercial technologies be seized by the government as part of an “enforcement” regime that would necessarily occur “on an unprecedented scale”.

This kind of thing has been tried before and it never turns out well for anyone who isn’t an insider of the enforcement regime. Joy seemed not to have been paying attention during the bloody history of 20th century.

I have always been instinctively suspicious of people who demonstrate an eager attraction to controlling others. So during the question and answer session that day, I managed to get a turn at the microphone and took the opportunity to challenge the premise underlying Joy’s authoritarian instincts. I commented that day on the fact that governments and large bureaucracies routinely demonstrated breathtaking incompetence in almost any undertaking that didn’t involve breaking things or killing people. I asked him if it wouldn’t be better to multiply the resources of the kinds of people in the room that day to solve these perceived problems? How would putting everything into the hands of bureaucrats solve anything?

In raising this argument, though I didn’t know it at the time, I was essentially making the same argument that William F. Buckley used to make when he said, “I am obliged to confess I should sooner live in a society governed by the first two thousand names in the Boston telephone directory than in a society governed by the two thousand faculty members of Harvard University.”

What prompted this essay now, eighteen years later, is the realization that similar doomsday prognostications are being offered in our time regarding artificial intelligence and, not coincidentally I suspect, free speech. And the prescriptions are ever the same: place power in the hands of the few.

There always seems to be a desire on the part of the few to control and manage the many. For some, the instinctive reaction to the unknown is always - always - to put things under the thumbs of people like themselves.

The internet started out as a fully distributed, highly redundant system designed to tolerate and route around failures. Resiliency was baked into the design and was done so to provide continued communications in the face of large-scale gaps in the interconnect fabric of the network itself. Essentially, the government and military wanted to maintain working command and control systems in the event of nuclear war.

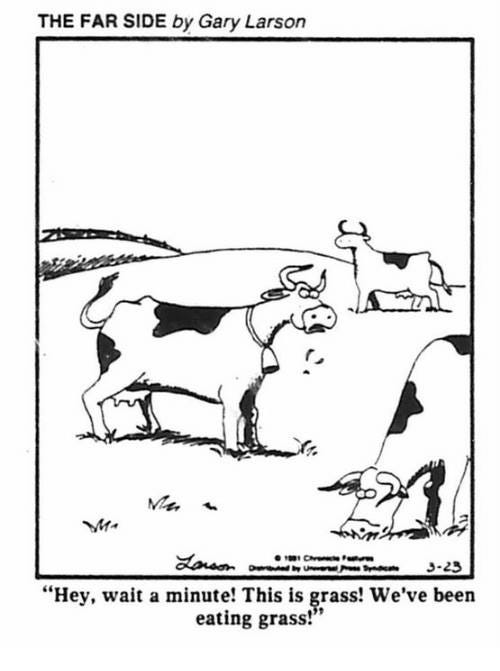

When the internet was commercialized in 1994, it initially had a democratizing effect in which information was highly diffused throughout the network itself and no one had control of anything. But over time, a handful of giant companies has successfully enticed the majority of users into these companies’ own walled gardens. This has had the effect of diminishing the democratic aspects of the network design. It’s as if the cows, having briefly escaped from the feedlot, have been lured back inside the fence with free hay. In the case of the internet, the hay takes the form of “free” services (e.g. email, picture storage, maps and navigation, etc.) Like cows all over the world, many social media users have embraced the belief that feedlots magically produce hay, not realizing that what a feedlot actually produces is dead cows.

Facebook and Twitter, among other operators of feedlots, have now begun to unilaterally eliminate some of the cows. On the heels of de-platforming, shadow banning, and direct competition from the giants themselves, people and companies who have made themselves dependent on these platforms are now discovering, to their horror, that the hay was never really free.

I am not suggesting that there aren’t some odious individuals and organizations leveraging these platforms to get their message out. I only mean to point out that the presumption of the feedlot operators is always that decisions about culling the herd should be centralized into the hands of people like themselves.

Feedlots are not entities designed to embrace the marketplace of ideas, allowing the marketplace to self-police itself by muting the influence of bad ideas. Rather than creating a platform in which ideas can compete on their merits, what the feedlot operators are actually doing is operating a managed platform to assuage their own sensibilities and make money off the cows. Thus, their self image and their moral and material neediness requires them to censor and cull those cows they deem unattractive. They do not believe the herd will recognize bad ideas and make an informed choice on its own. The herd is just a bunch of cows, after all. Better to let the feedlot operator decide who gets the hay and who does not.

All of this behavior by the feedlot operators is reminiscent of Bill Joy’s view that the hairy unwashed just can’t be trusted with certain technologies and people who share his views should be in charge of “enforcement”. In the 18 years since Joy’s prediction of doom, none of his fears have been realized. And though his predictions have so far failed to come true, his authoritarian prescription remains as attractive as ever to a certain kind of controlling personality.

People will, of course, inevitably use technology to achieve evil ends. Social media is populated with so many people that someone will inevitably spout some sort of evil nonsense. But it doesn’t necessarily follow that the way to combat such evil is for a few rich programmers in California to act as censors. Programmers, of all people, have never been known for their social and moral acumen anyway. There are no super humans instilled with super powers, uniquely equipped to be overseers of everyone else. When we centralize power into the hands of the few, we adopt a cure that is invariably worse than the disease. For as C.S. Lewis wisely observed decades ago:

“Aristotle said that some people were only fit to be slaves. I do not contradict him. But I reject slavery because I see no men fit to be masters.”

The high-handed behavior of the internet giants should tell you all you need to know about their opinion of us cows.